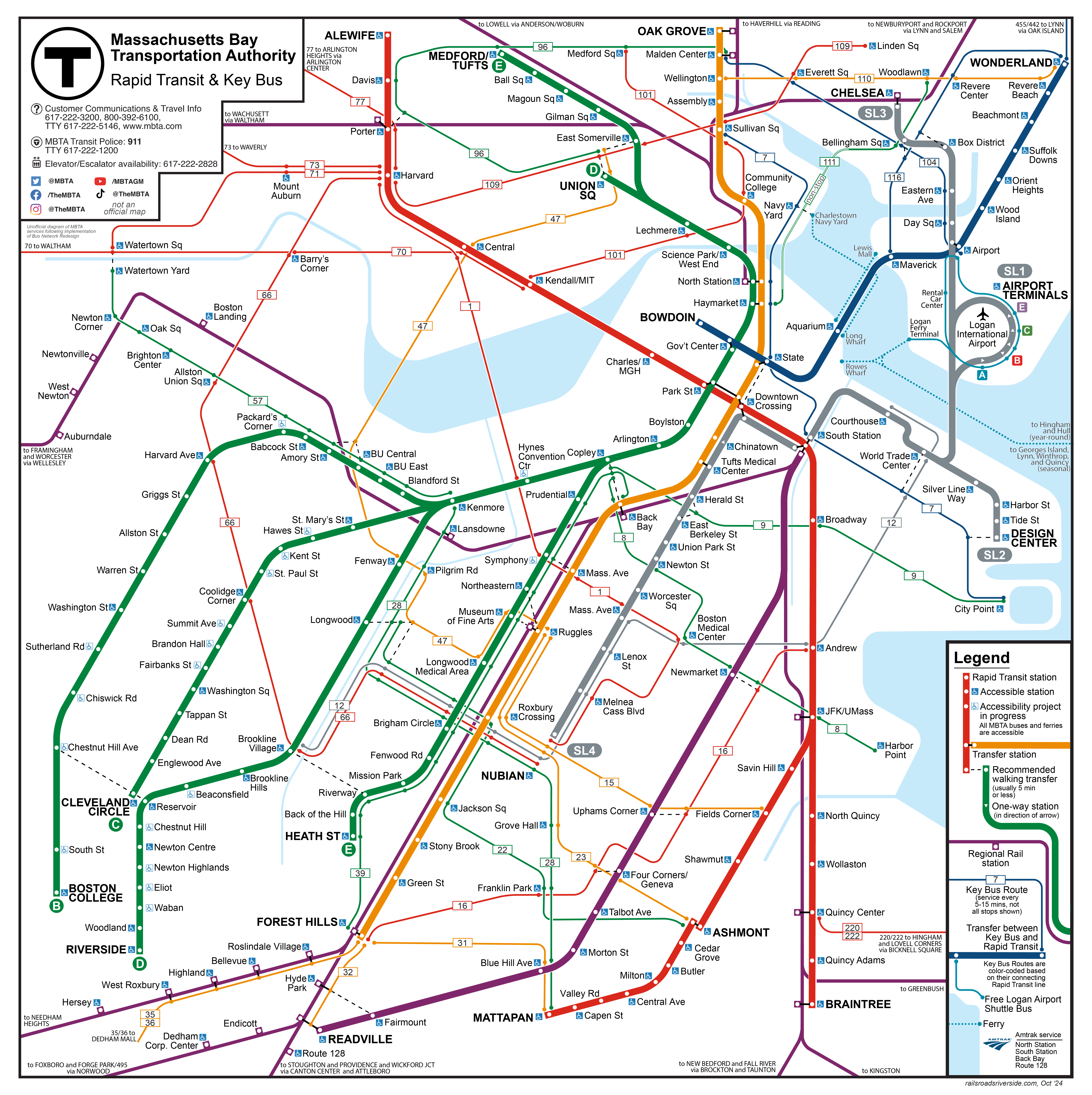

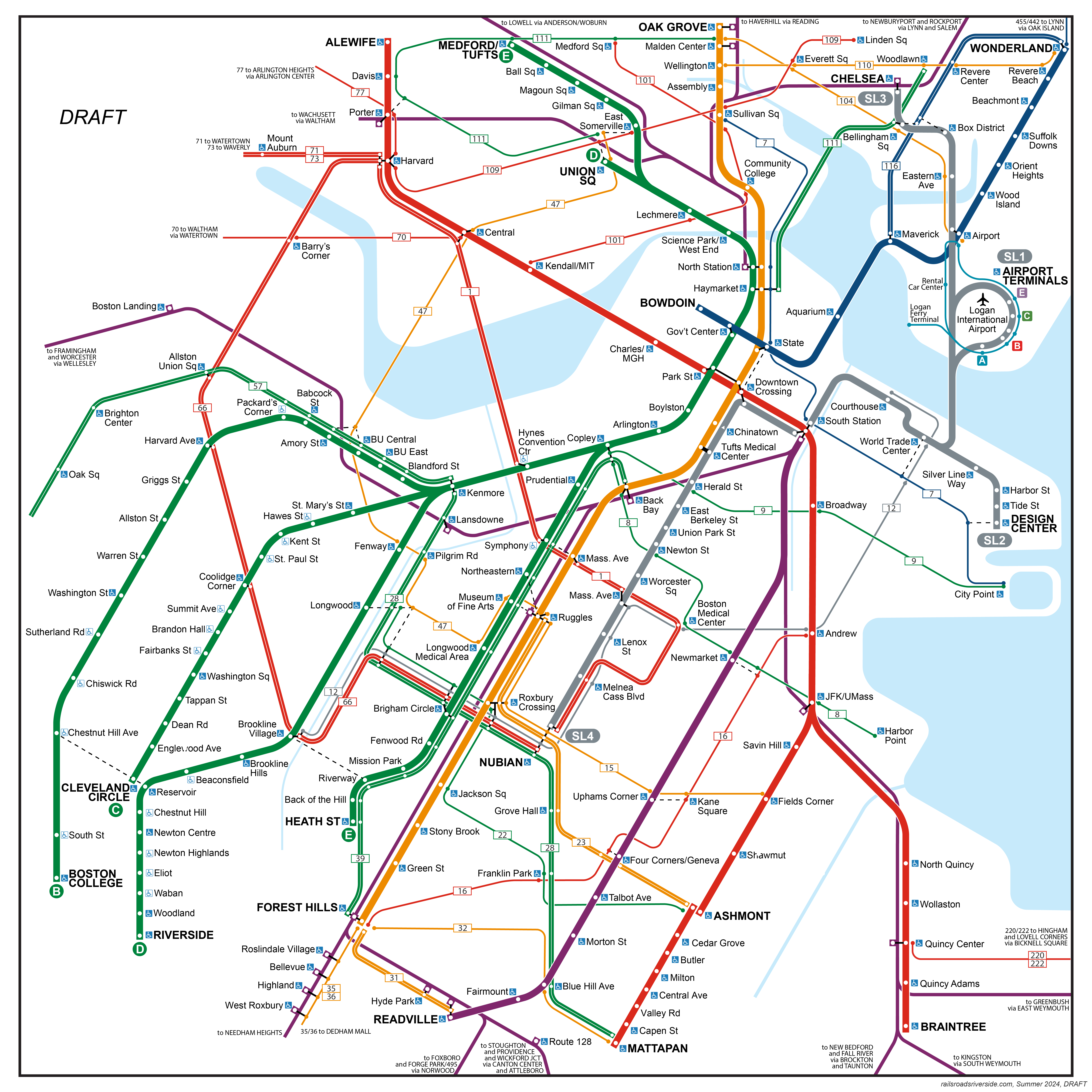

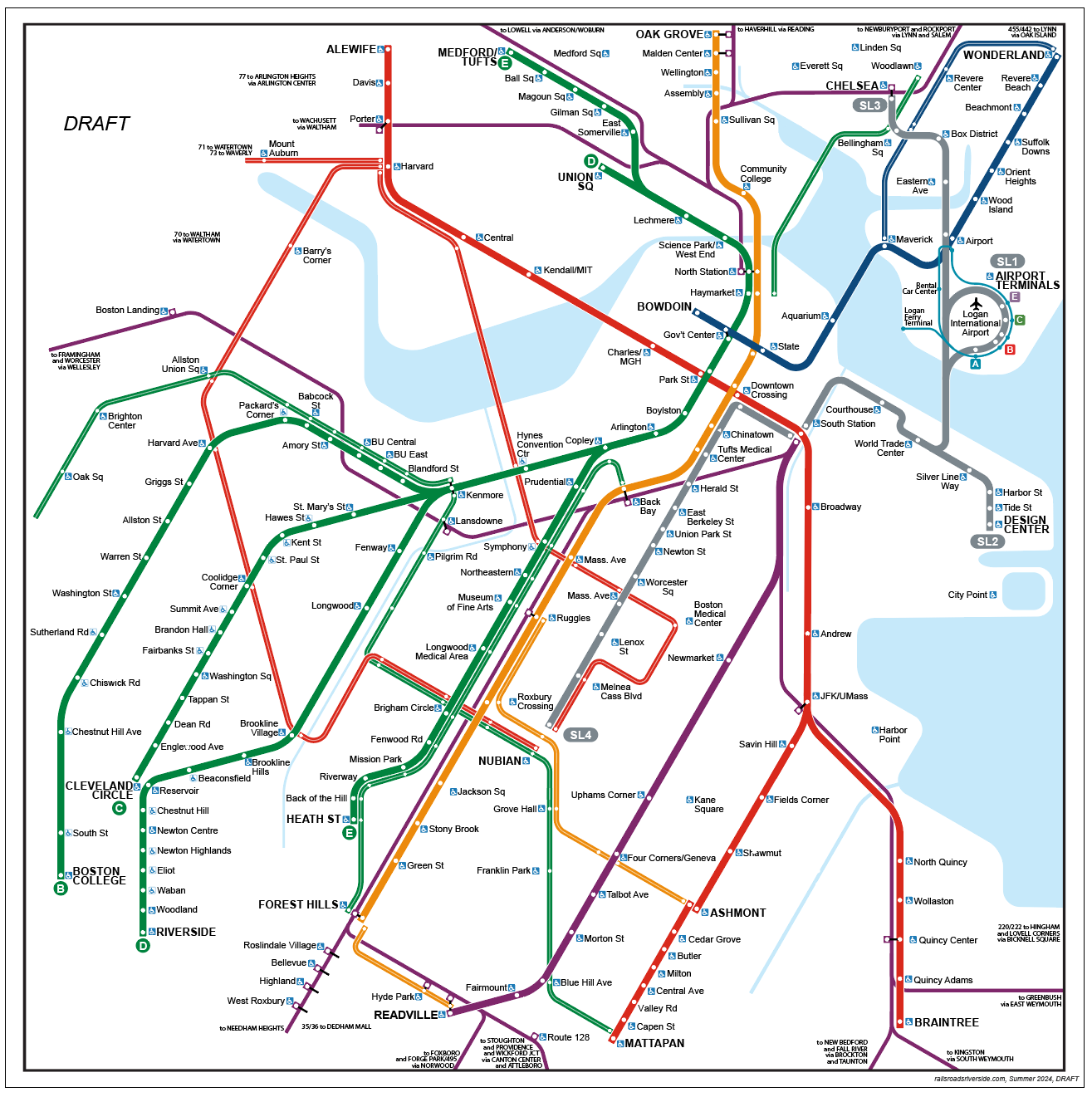

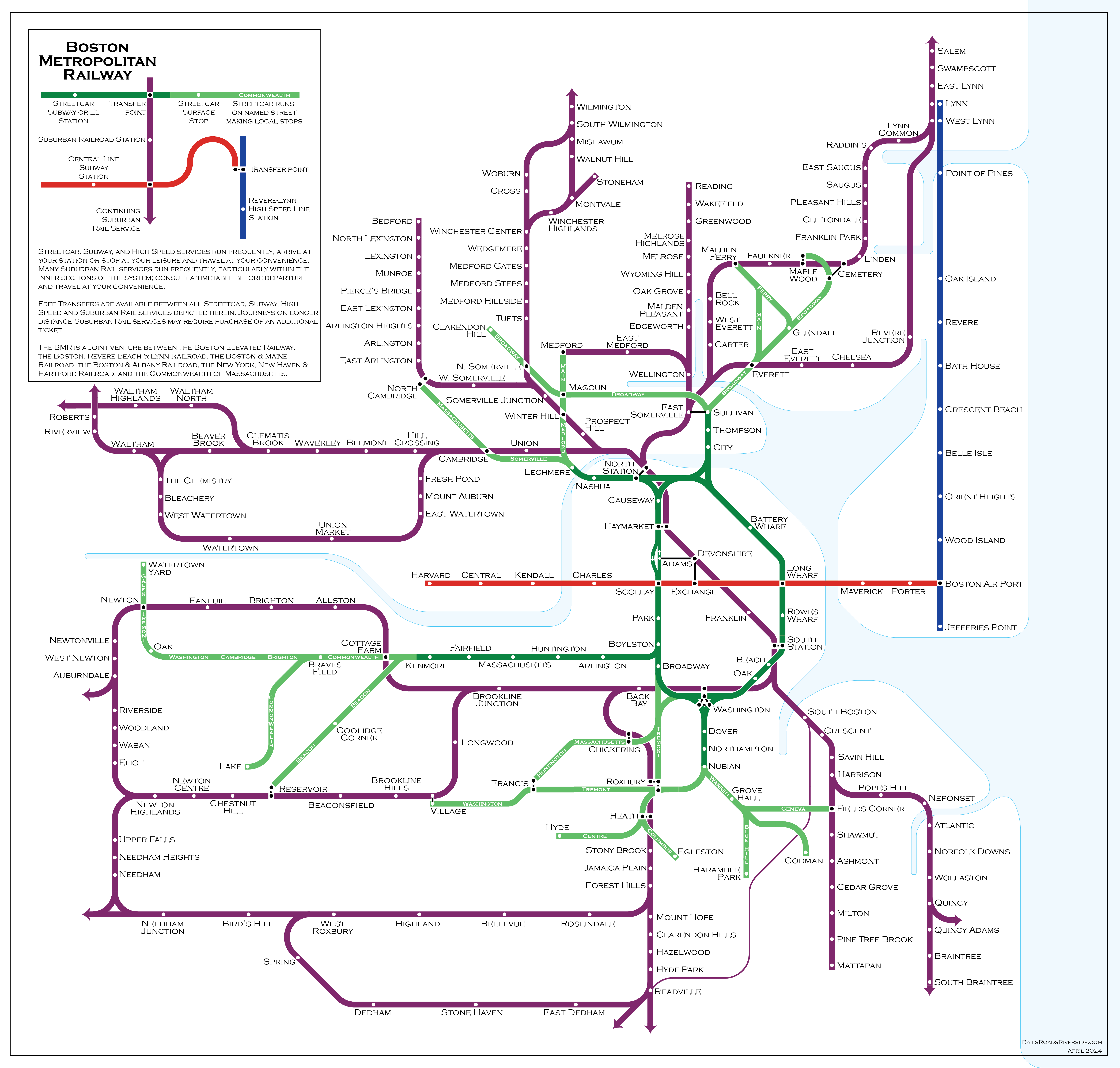

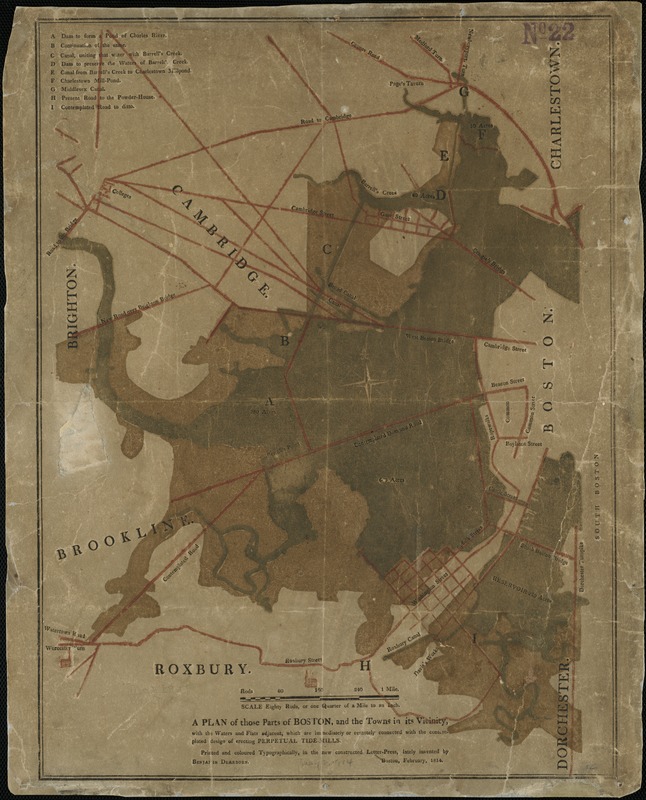

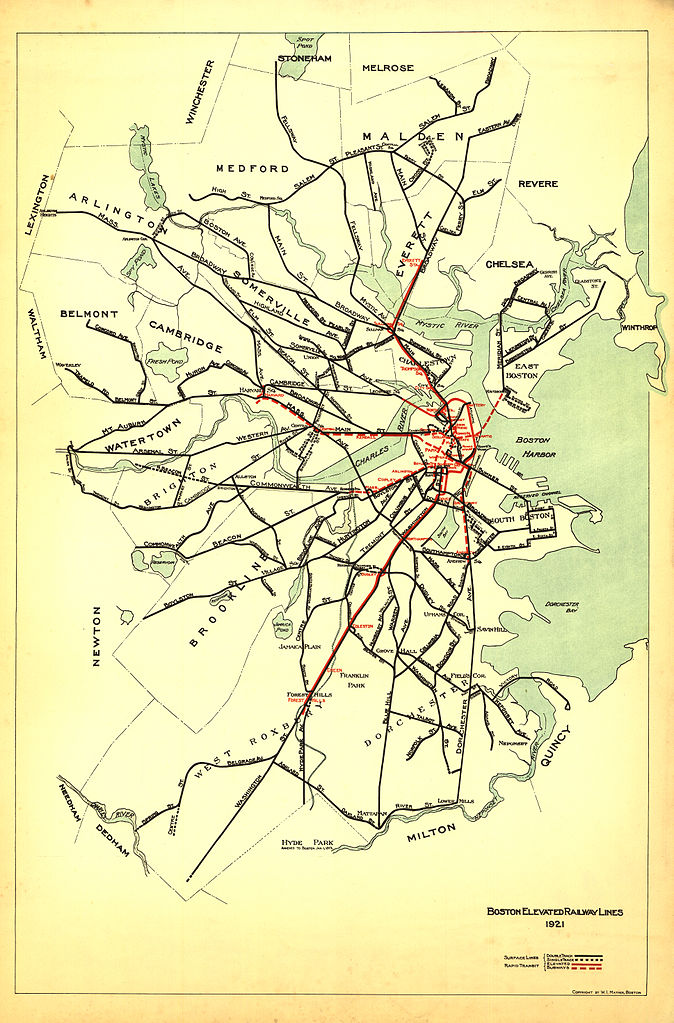

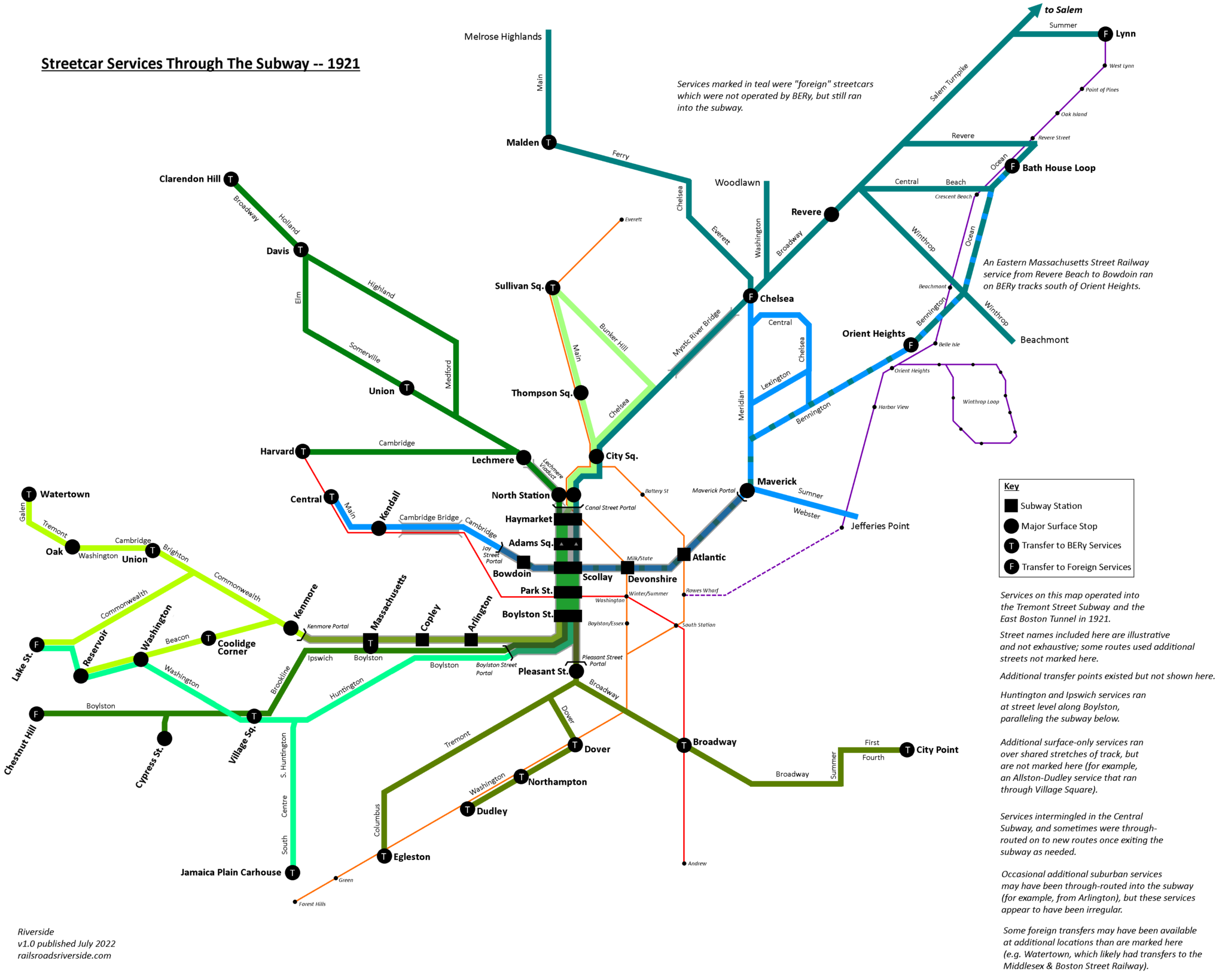

In the 1910s and early 20s, the Boston Elevated Railway Company (BERy, predecessor to the MTA and MBTA) expanded and modified their streetcar subway, making critical additions that transformed it into something recognizable as an early version of the Green Line.

I have written about these changes in the past, but want to briefly summarize the two models that emerged from BERy’s modifications. In both cases, BERy was trying to address the problem of long trolley routes that stretched from the suburbs all the way into downtown, running slowly at street level, usually in mixed traffic, the buses of their day. The original Tremont Street Subway was built with the relatively narrow goal of getting trolleys off of downtown’s congested streets. BERy’s expansions broadened the scope of the streetcar subway significantly.

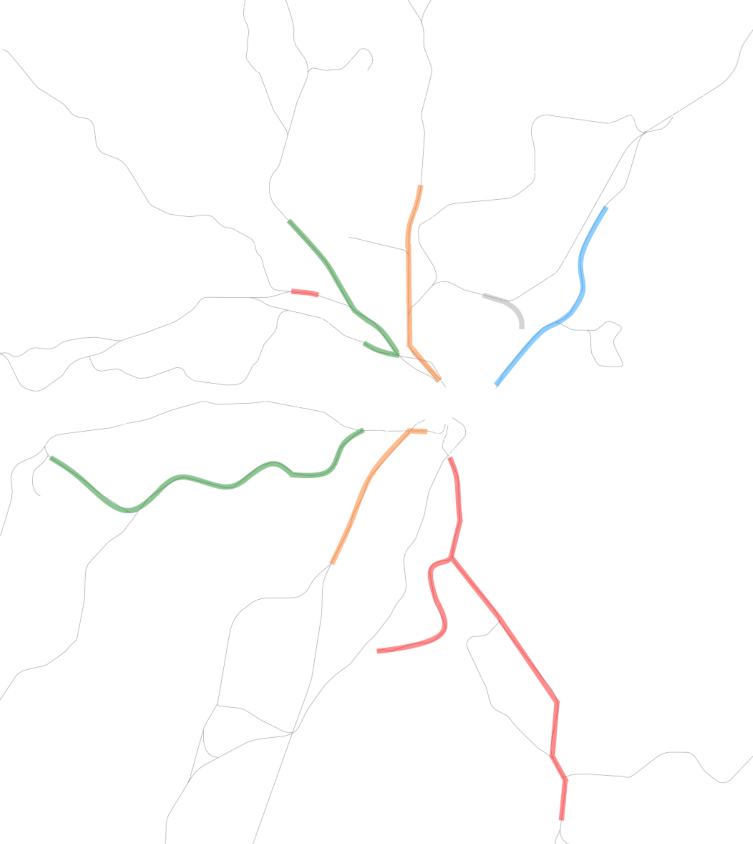

Kenmore Model

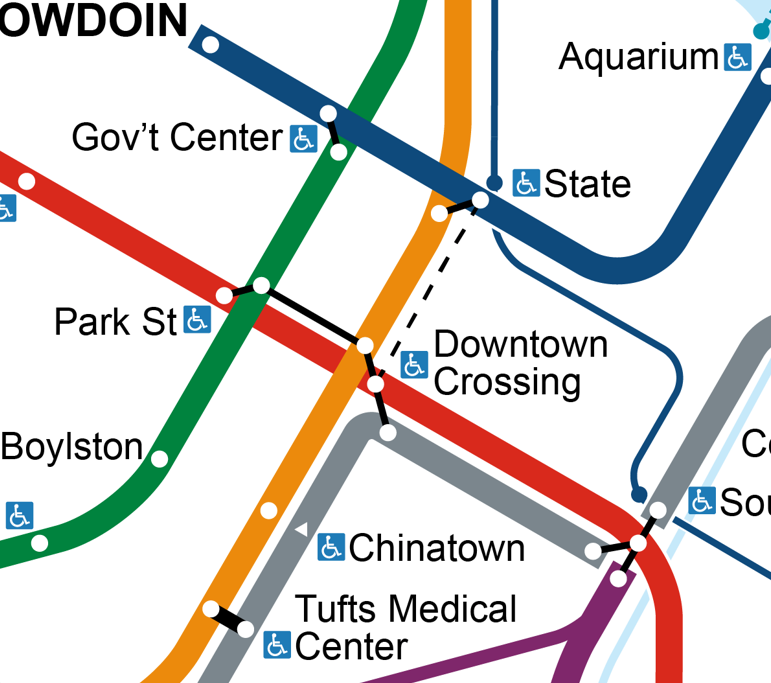

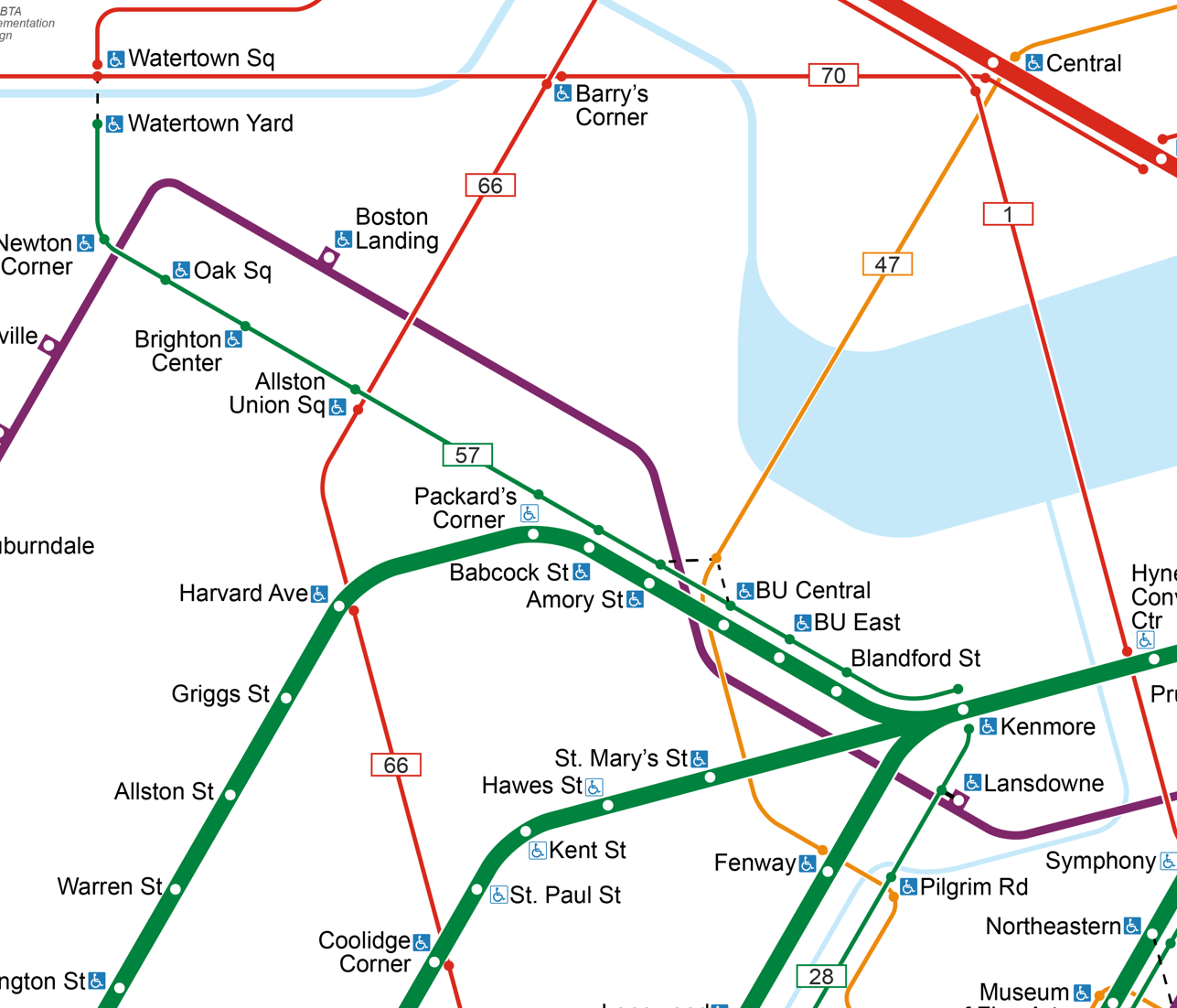

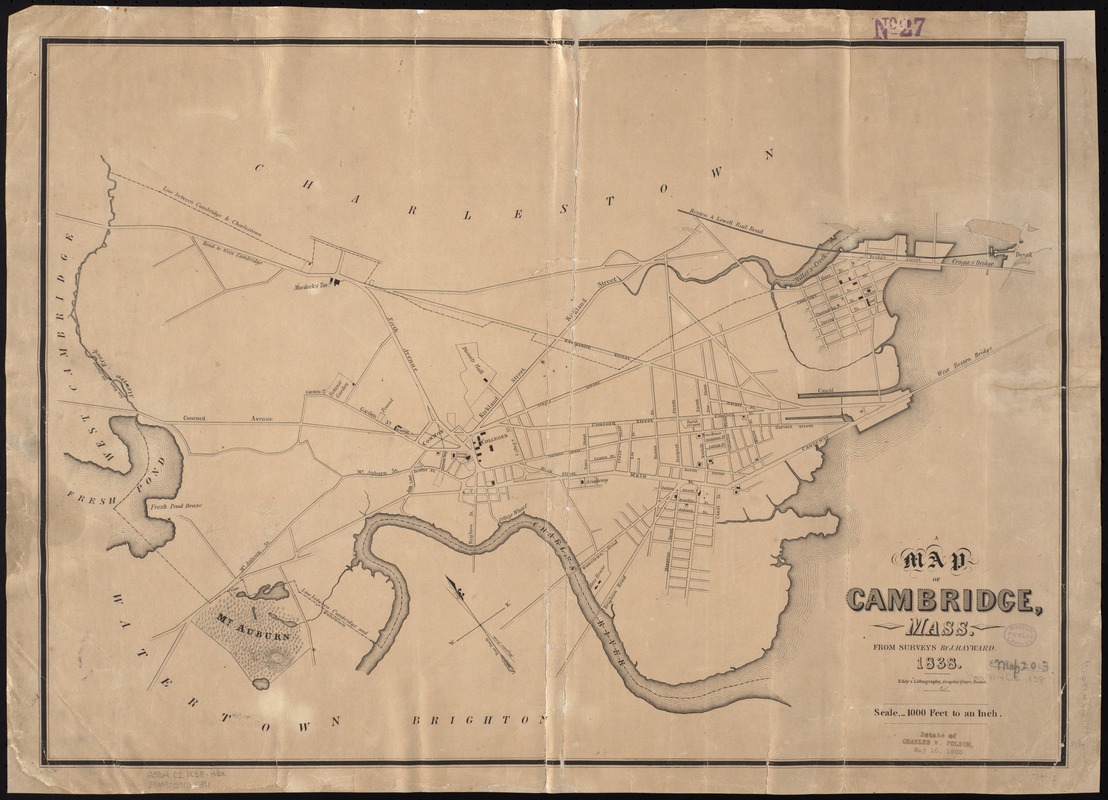

To the west ran some of the oldest surface lines in Greater Boston, the predecessors to today’s B and C Lines, and the now defunct A Line. When the Tremont Street Subway first opened, these trolleys trundled all the way down Boylston St at surface level, entering the subway at the Public Garden Incline between Arlington St and Charles St.

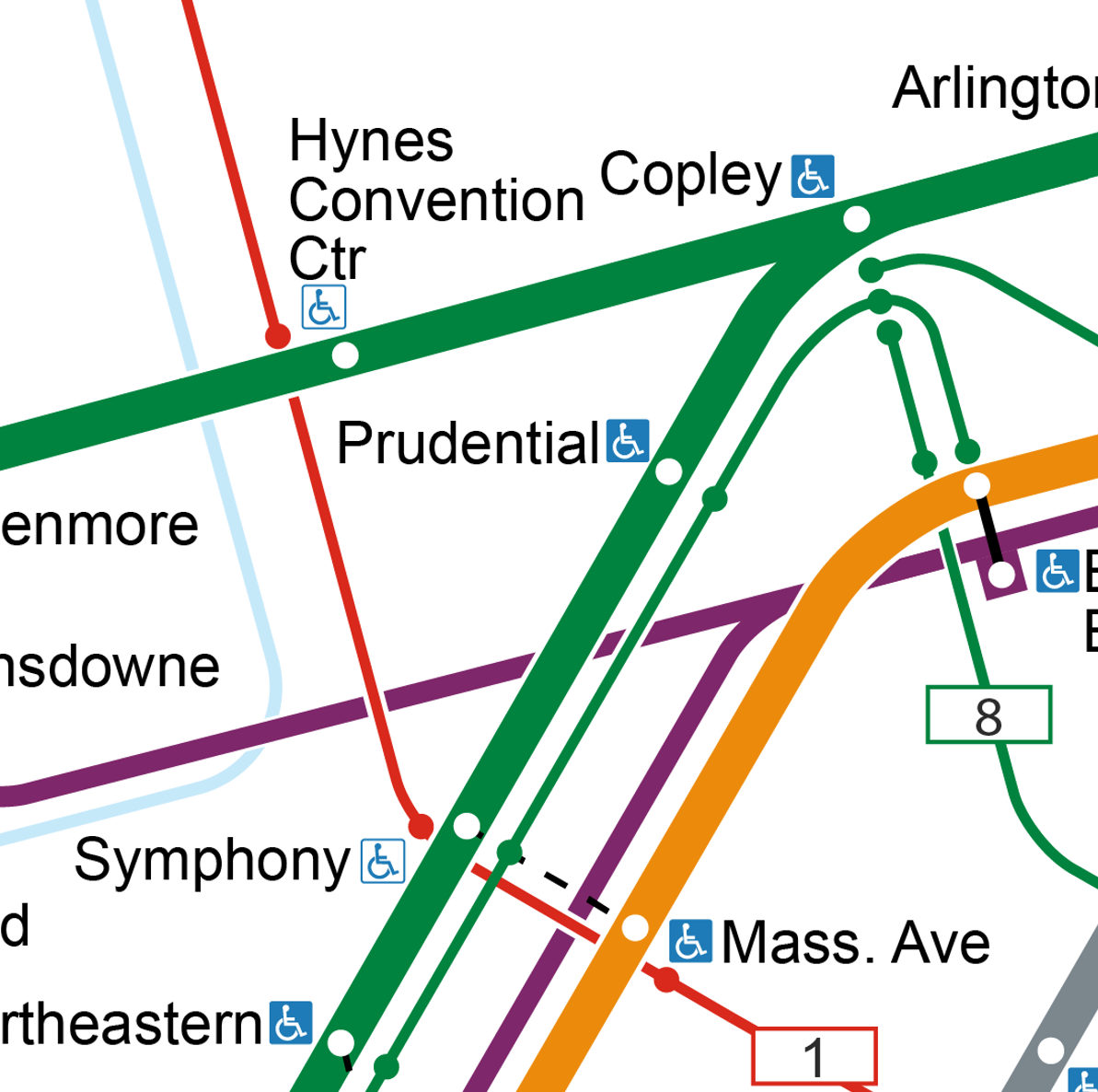

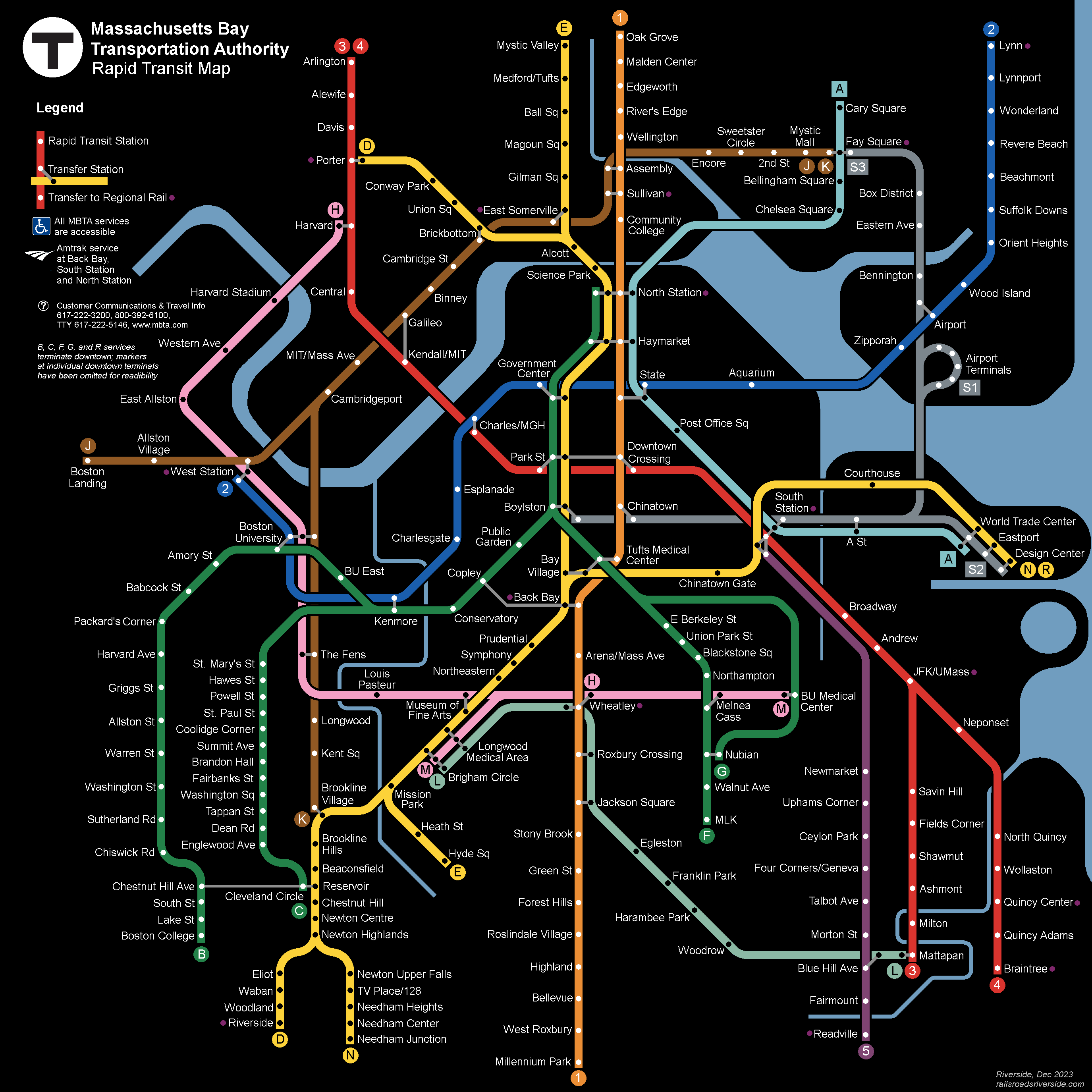

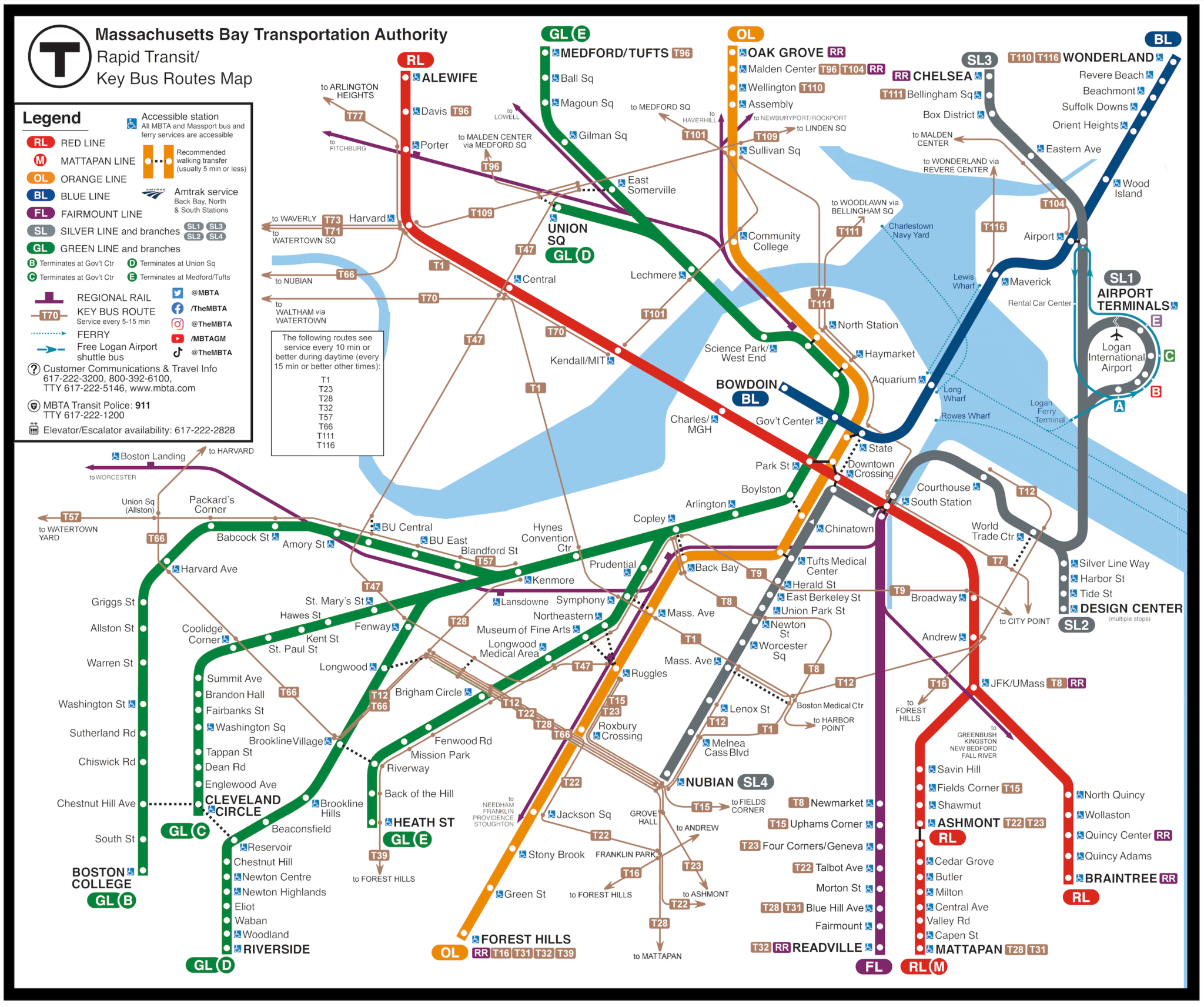

In 1914, the Boylston Street Subway opened, adding a new tunnel that extended through Back Bay with stations at Copley and Massachusetts (now Hynes Convention Center) before emerging at the surface just before Kenmore Square. (A one-stop extension underneath Kenmore Square opened about twenty years later, giving us the station we know today.)

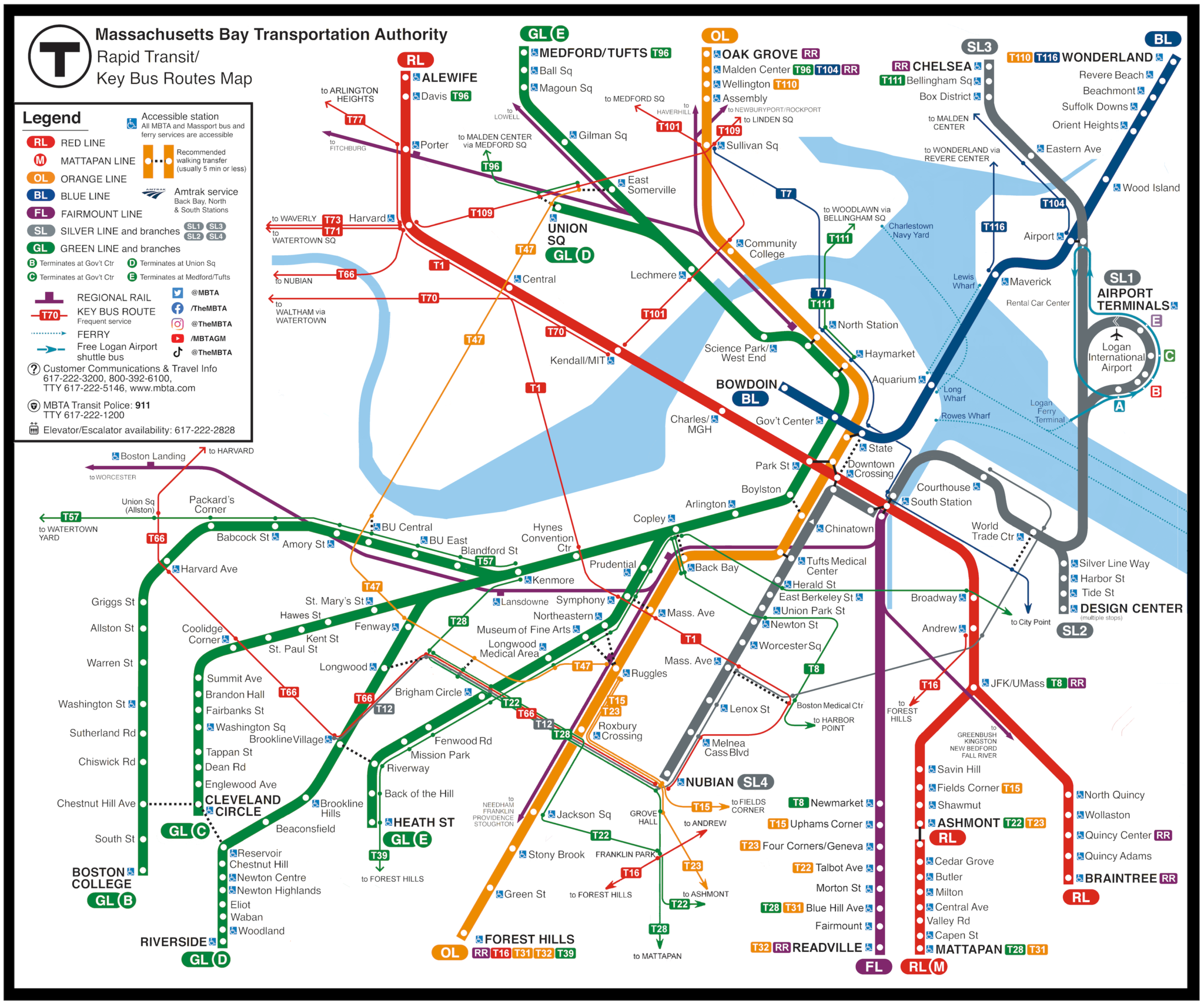

The proto-A, B, and C Lines thereafter entered the portal at Kenmore and ran “express” underground into downtown. Other shorter distance routes continued to operate into the now-relocated Public Garden Incline, but those longer distance routes were given a (comparatively) high speed bypass.

This was BERy’s first attempt to address the needs of suburban surface lines. Under the Kenmore Model, surface routes run like buses before entering a subway in which streetcars run in a dedicated ROW at high speed into downtown, often producing rapid transit-like service as multiple routes layer to form very high frequencies.

The two other legacy streetcar subway networks in the US – San Francisco’s MUNI Metro and Philadelphia’s SEPTA – also utilize the Kenmore Model. The need to travel underground is arguably what spared these systems from “bustitution”, since buses couldn’t adequately run in the subways.

(San Francisco’s Kenmore Model is actually somewhat coincidental: its Market Street Subway, which mimics the Boylston Street Subway, wasn’t built until the late 1960s; instead, the need for streetcars in order to utilize the Twin Peaks Tunnel, to the west, was likely the protective factor in that system.)

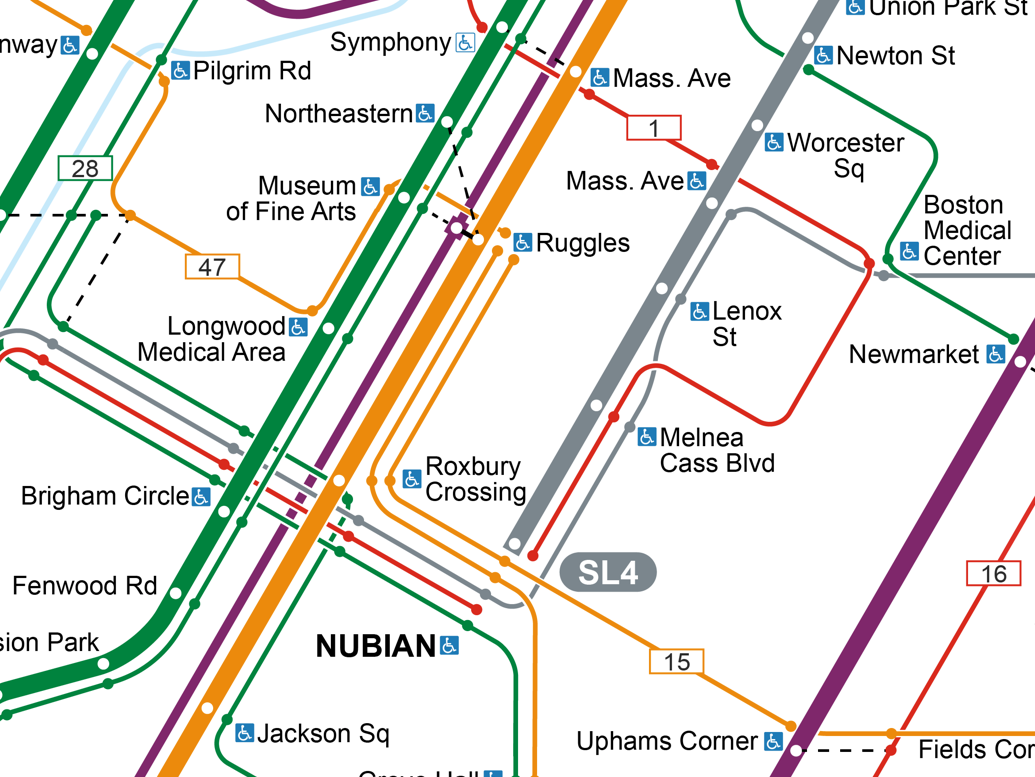

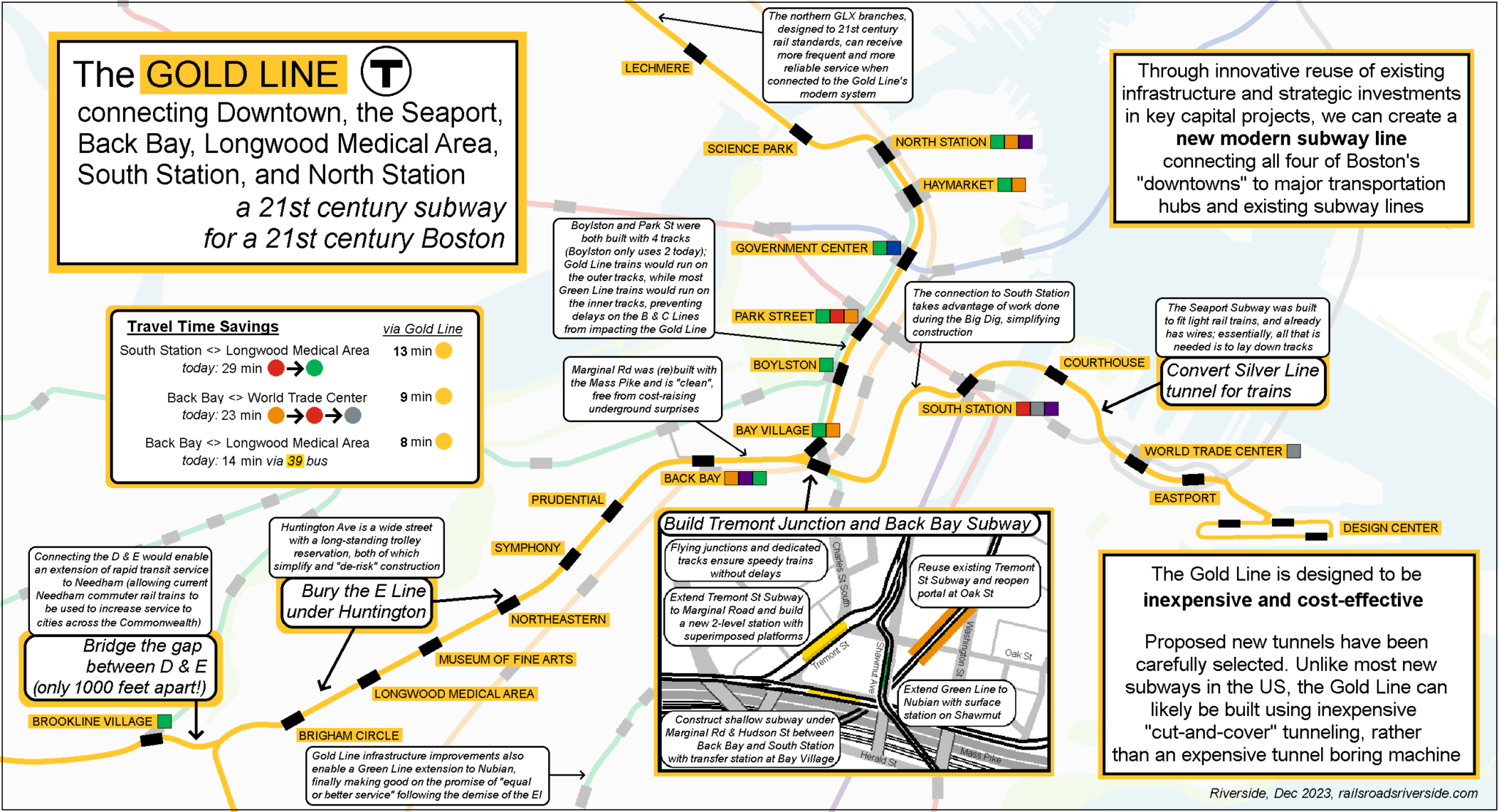

The Kenmore Model’s persistence today creates an odd inequity, where residents of Brookline and Allston get to enjoy the convenience of a surface route (with frequent, nearby stops) with a one-seat ride directly into downtown. Residents of neighborhoods much closer to downtown (such as Roxbury) do not enjoy that benefit.

EDIT: I am reminded the Pittsburgh also enjoys a long-surviving first generation streetcar system. Topologically, it’s similar to the Kenmore Model, with a lengthy subway running into the core. However, after leaving the subway, the Pittsburgh Light Rail branches operate primarily on dedicated railroad ROWs, with rapid transit spacing. For this reason, I would not classify Pittsburgh Light Rail as a “streetcar subway”, its street-running segments notwithstanding. Its at-grade routes do not behave like buses the way that the T’s, SEPTA’s, and MUNI Metro’s do. In that sense, the term “Kenmore Model” isn’t applicable.

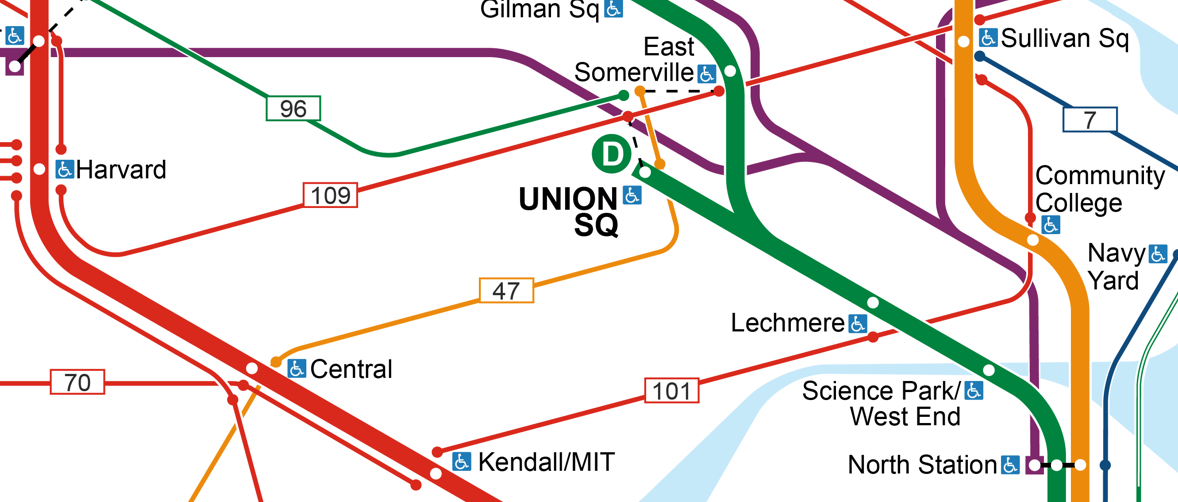

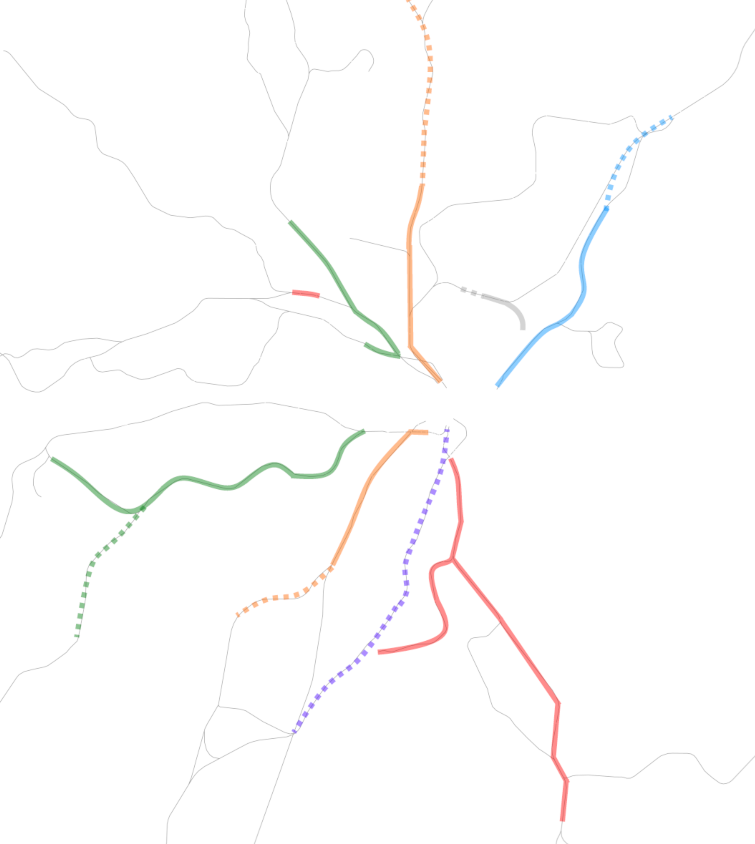

Lechmere Model

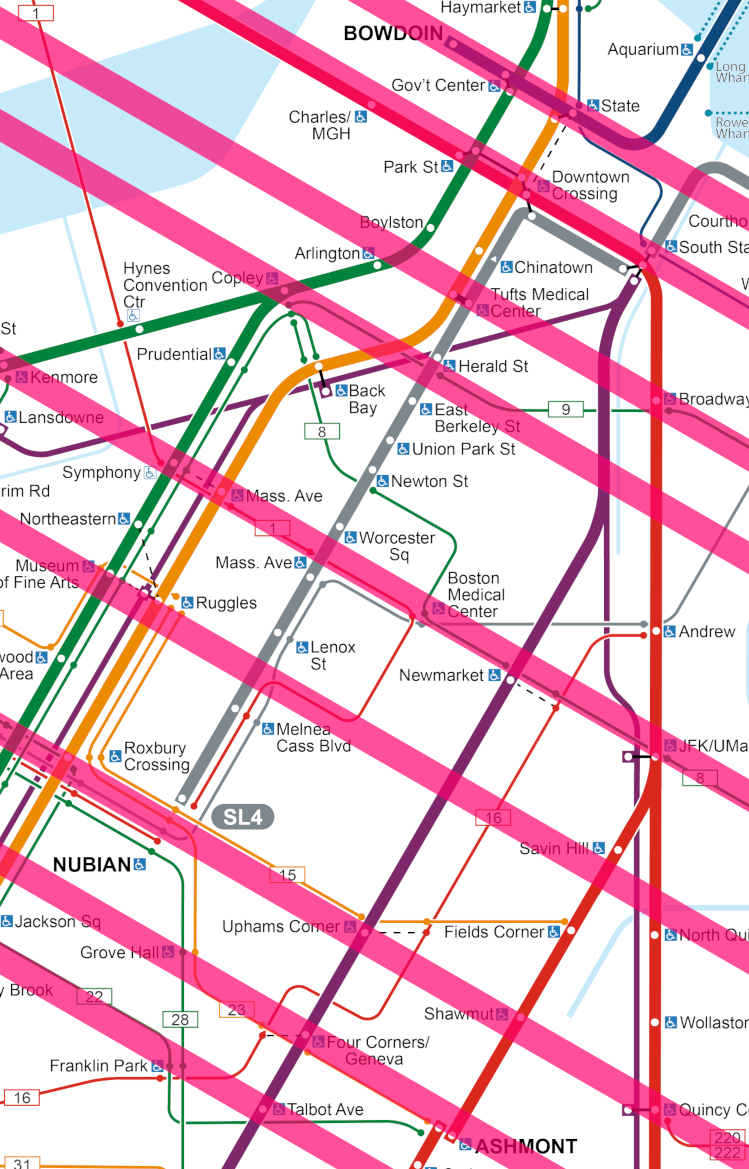

When BERy extended their dedicated streetcar ROW out of the subway at Haymarket north to an elevated along Causeway Street and across the Charles River, they initially employed the Kenmore Model at Lechmere as well. Streetcars from Harvard Square, Union Square, Davis Square, and Clarendon Hill ran directly from street-level on to the viaduct and eventually into the subway.

In 1922, BERy constructed a transfer terminal at Lechmere Square. Surface cars from the northwest terminated at what became the bus terminal, while cars coming from the subway looped within the dedicated ROW of the station. This marked a key transformation in BERy’s treatment of its streetcar subway, now treating it as a service that could potentially act as rapid transit.

The Lechmere Model mirrored BERy’s approach at its other rapid transit terminals. At Sullivan, Harvard, Dudley, and Maverick, surface routes that had once run all the way into downtown were truncated, with riders transferring to high-speed rapid transit service. This model remains in use across the system today.

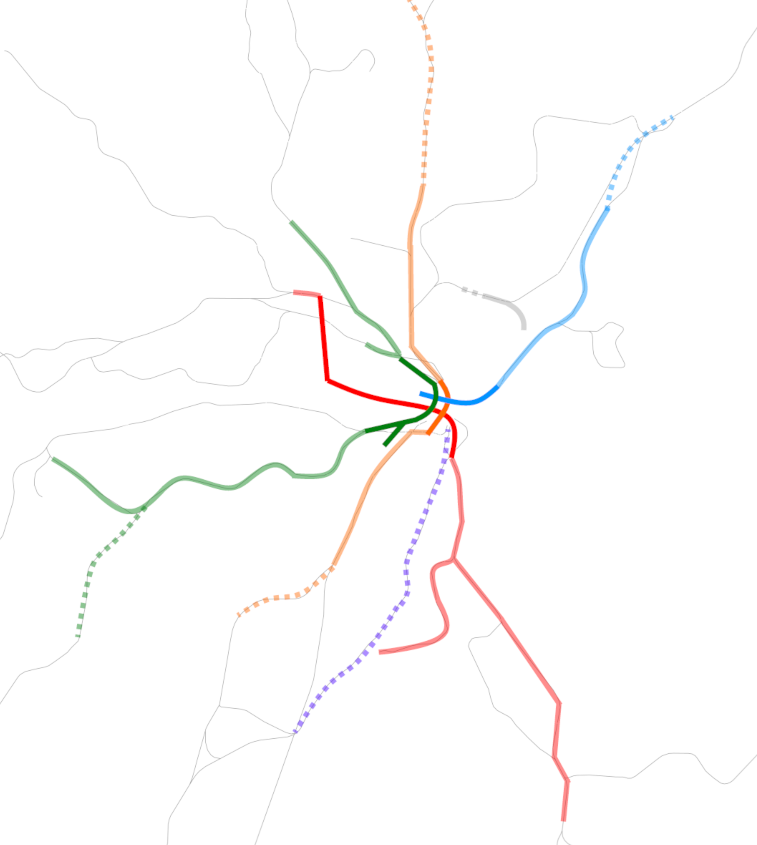

BERy intended to eventually deploy a Lechmere Model approach in the Kenmore area as well. The C would have been truncated to the Kenmore Loop, while the Central Subway itself would’ve been converted similarly to the Blue Line, and extended to a transfer station in Allston to meet truncated versions of the A and B. Obviously, that never happened.

Broader Implications

The Lechmere and Kenmore Models speak to the various factors that govern a transit service’s character:

- The dedicated ROW of a subway or elevated, versus (semi-)mixed traffic-running at surface level

- The close stop spacing of a slower surface line, versus the fast speed of a subway line with fewer stops

- The rider experience of a one-seat ride, versus transferring at a hub

Both models present benefits and drawbacks. The B and C are among the highest ridership surface routes, in favor of the Kenmore Model. After the opening of Lechmere Terminal, BERy was able to run higher-capacity cars in the subway. On the other hand, reliability in the Central Subway is impacted by the amalgamation of multiple surface routes; and transfers exact a penalty on both ridership and rider experience.

Differentiating between the Kenmore and Lechmere Models allows for a more precise analysis of existing services and potential future expansions.

Addendum

Dec 21 2024

Following discussion on ArchBoston, I’m adding two additional models to the framework above.

Tremont Model

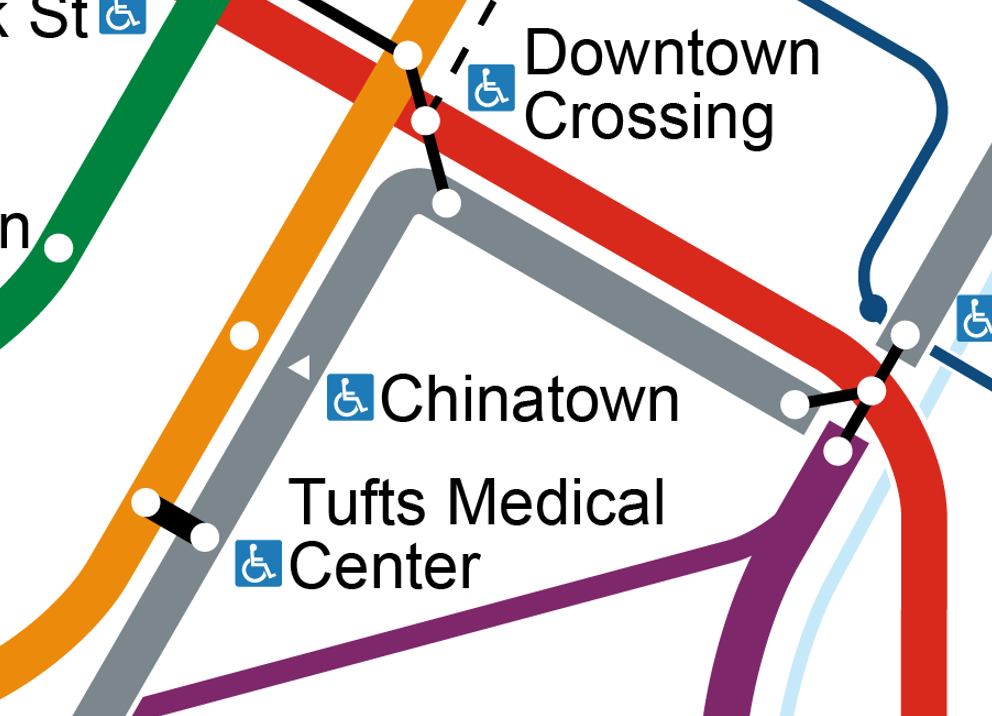

This was the original model of the Tremont Street Subway, whose purpose was simple: just get the dang trolleys off of downtown’s streets.

The Tremont Model is marked primarily by having a short distance of grade-separated ROW through a congested core. Rapid transit-like features may emerge, but as a side effect rather than an objective.

The Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel operated under the Tremont Model for about 25 years before being converted exclusively to rapid transit-style light rail service. Bus routes from across the region converged and traversed downtown in their own grade-separated right-of-way. (Many of those buses also ran on highways, making them a bit less like the local streetcar service that originally ran into the Tremont Street Subway.)

The Newark City Subway historically would not have fit the Tremont Model, as its originally sole service ran in its own ROW on the surface with rapid transit stop spacing. However, with the opening of the Broad Street Extension, the network has now assumed characteristics of a Tremont Model, where a surface route making local stops enters a subway for a relatively short segment to avoid congestion on the surface.

Perhaps the clearest example of an extant Tremont Model is in Toronto (unsurprisingly), where a short streetcar subway runs from Union Station to Queens Quay before emerging to run at street level. Queens Quay in particular highlights a good example of the non-rapid transit goals of a Tremont Model subway: the station itself does not have fare control. Passengers pay as they board, just as they do on the street. This reflects the primary purpose of a Tremont Model: just get the surface vehicles off the street; any rapid transit-like results are secondary.

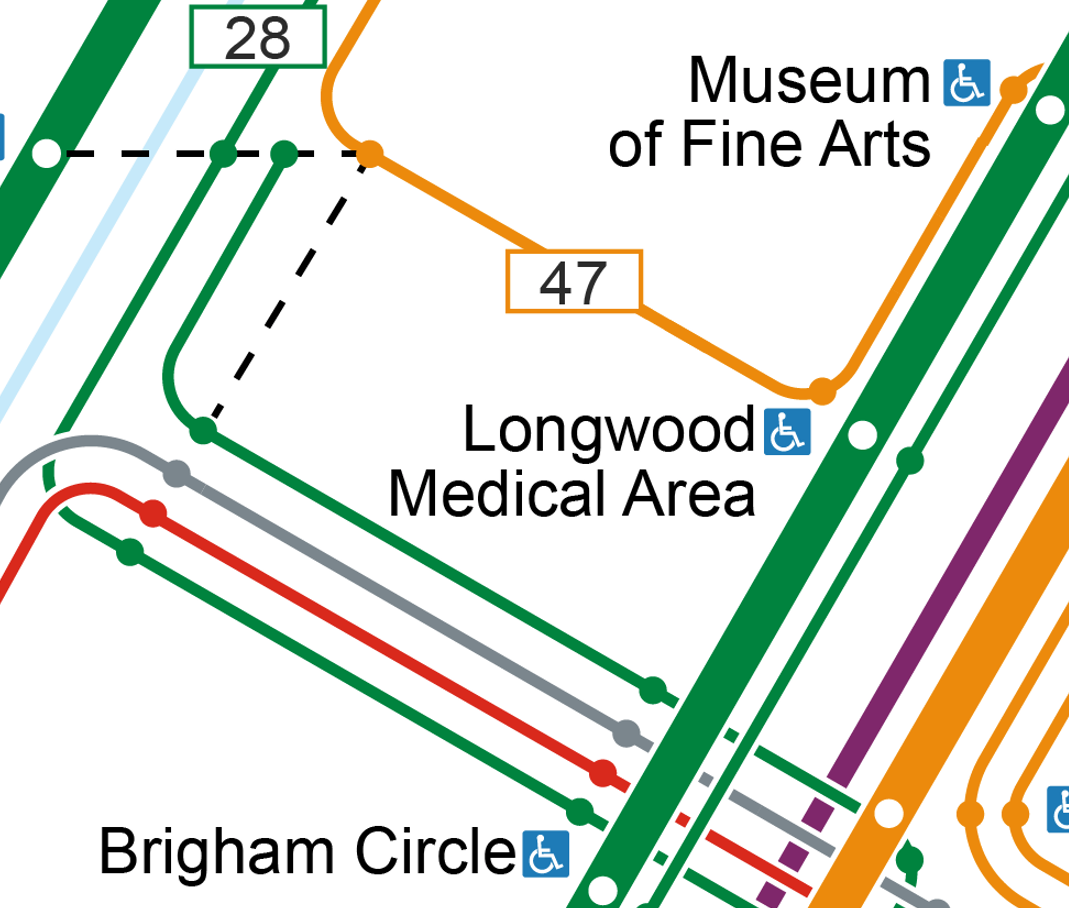

Medford Model

While the Medford Branch does feature bus connections, I argue that it does not prioritize integration with the surface network the way the Lechmere Model does. Its transfer points notwithstanding, none of its stops (aside from Lechmere) serves as a transfer hub or even a terminus point. Rather, the Medford Branch, particularly with its closer stop spacing, seeks to serve its suburbs directly, rather than relying on the 2SR of the Lechmere Model or the 1SR of the Kenmore Model.

The Medford Model was really first implemented on the Highland Branch in the 1950s when it was converted from a commuter rail line. As modern light rail lines acquire more and more characteristics and responsibilities of rapid transit, the Medford Model has emerged as a predominent model in the 21st century.