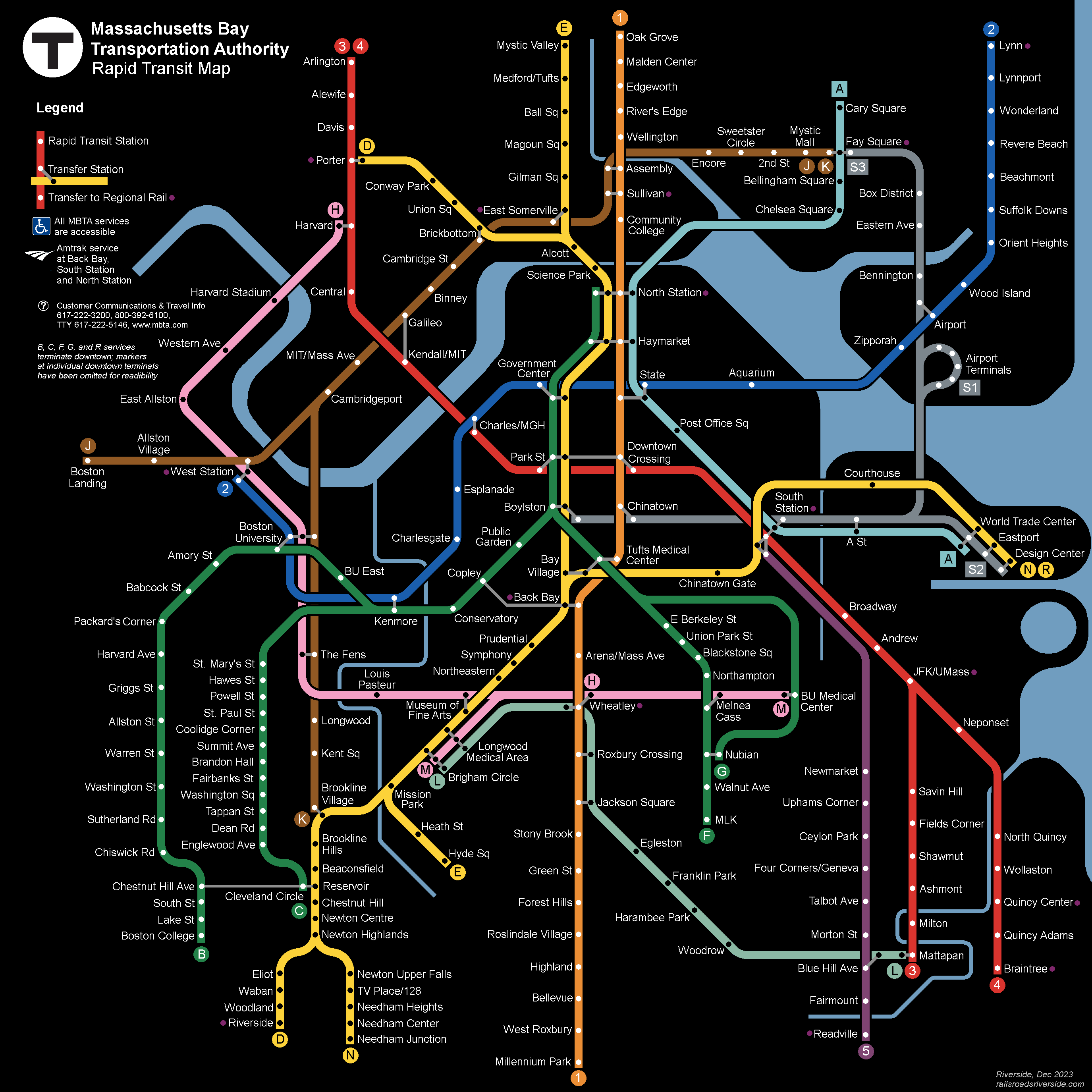

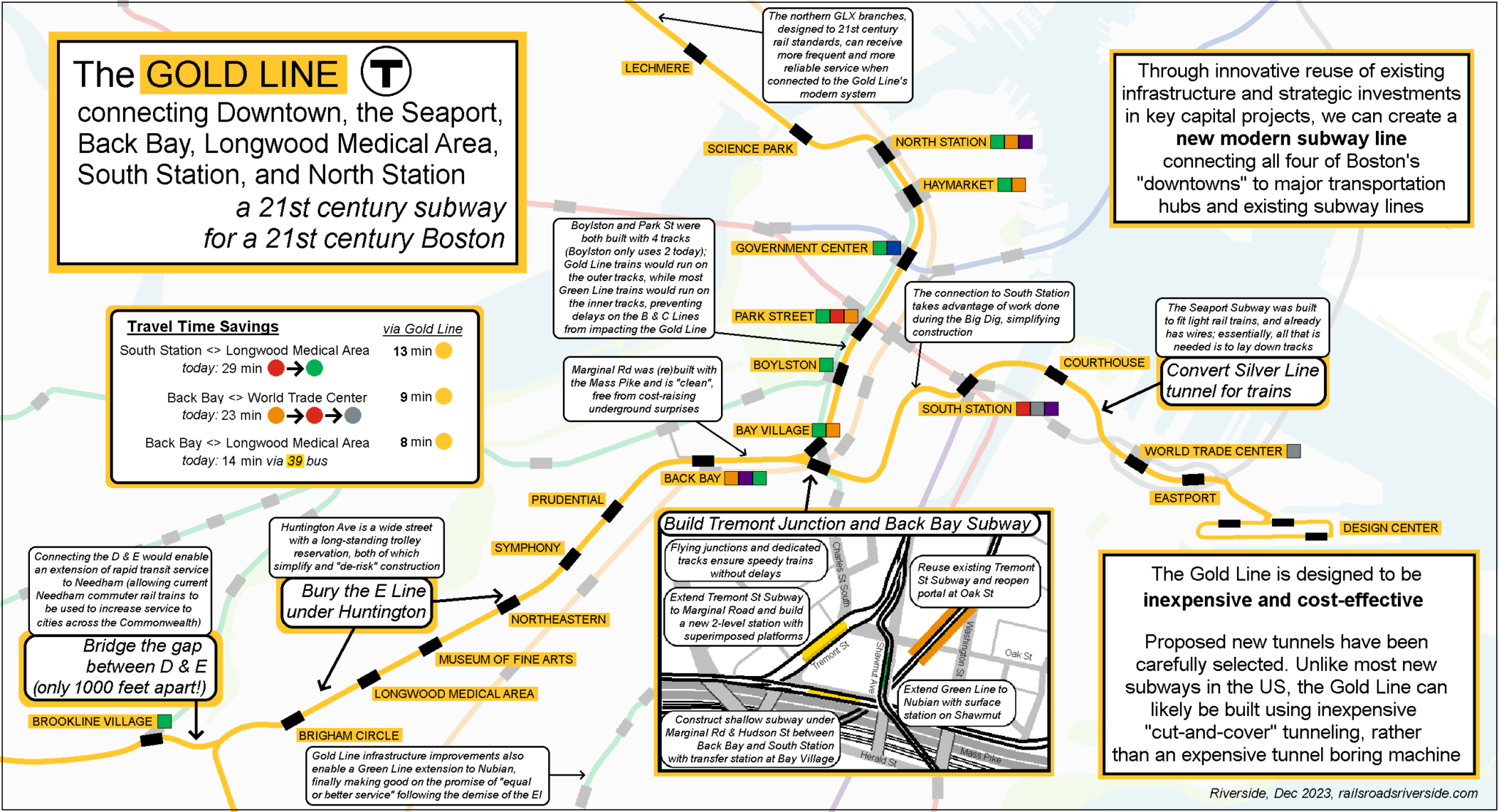

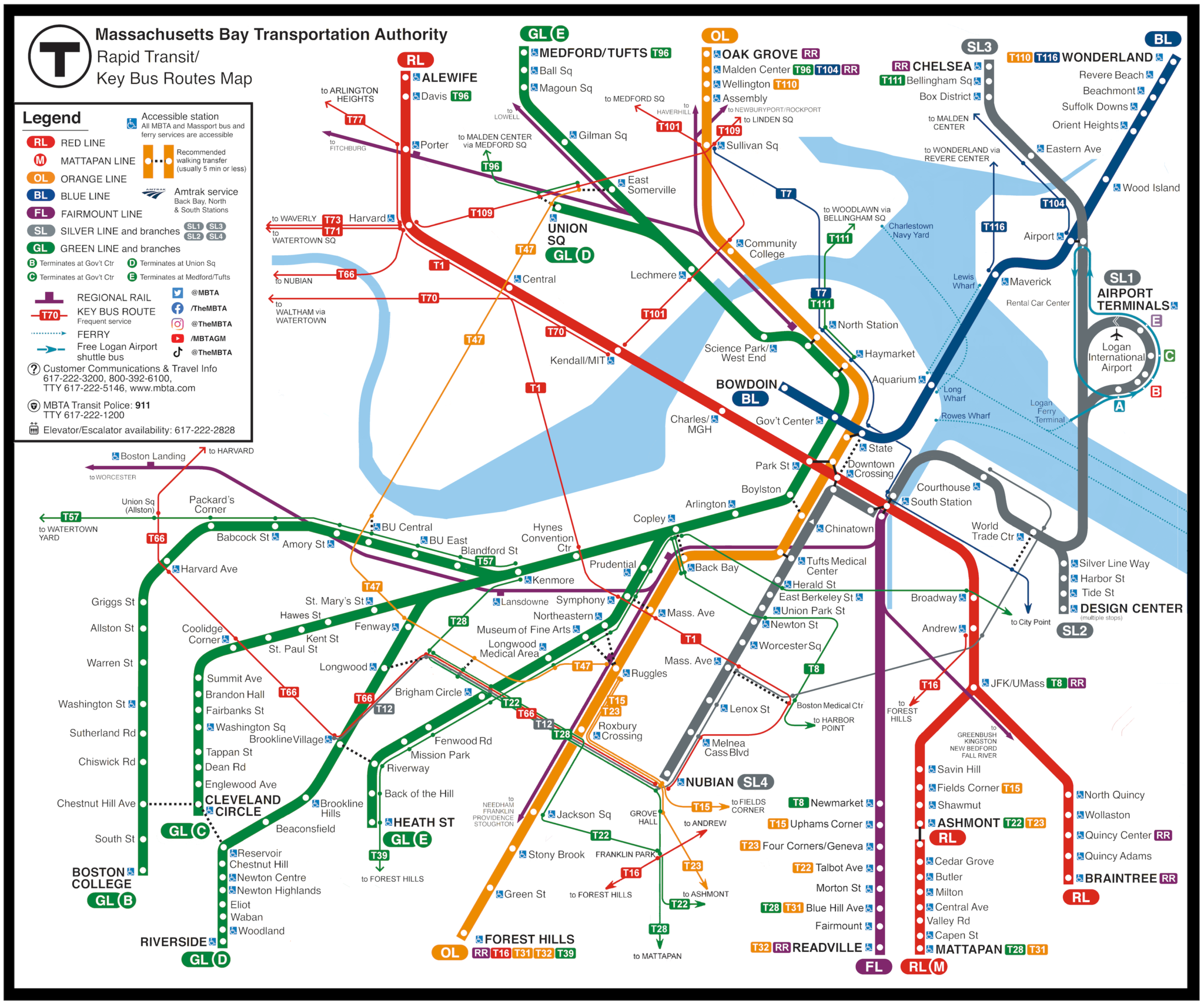

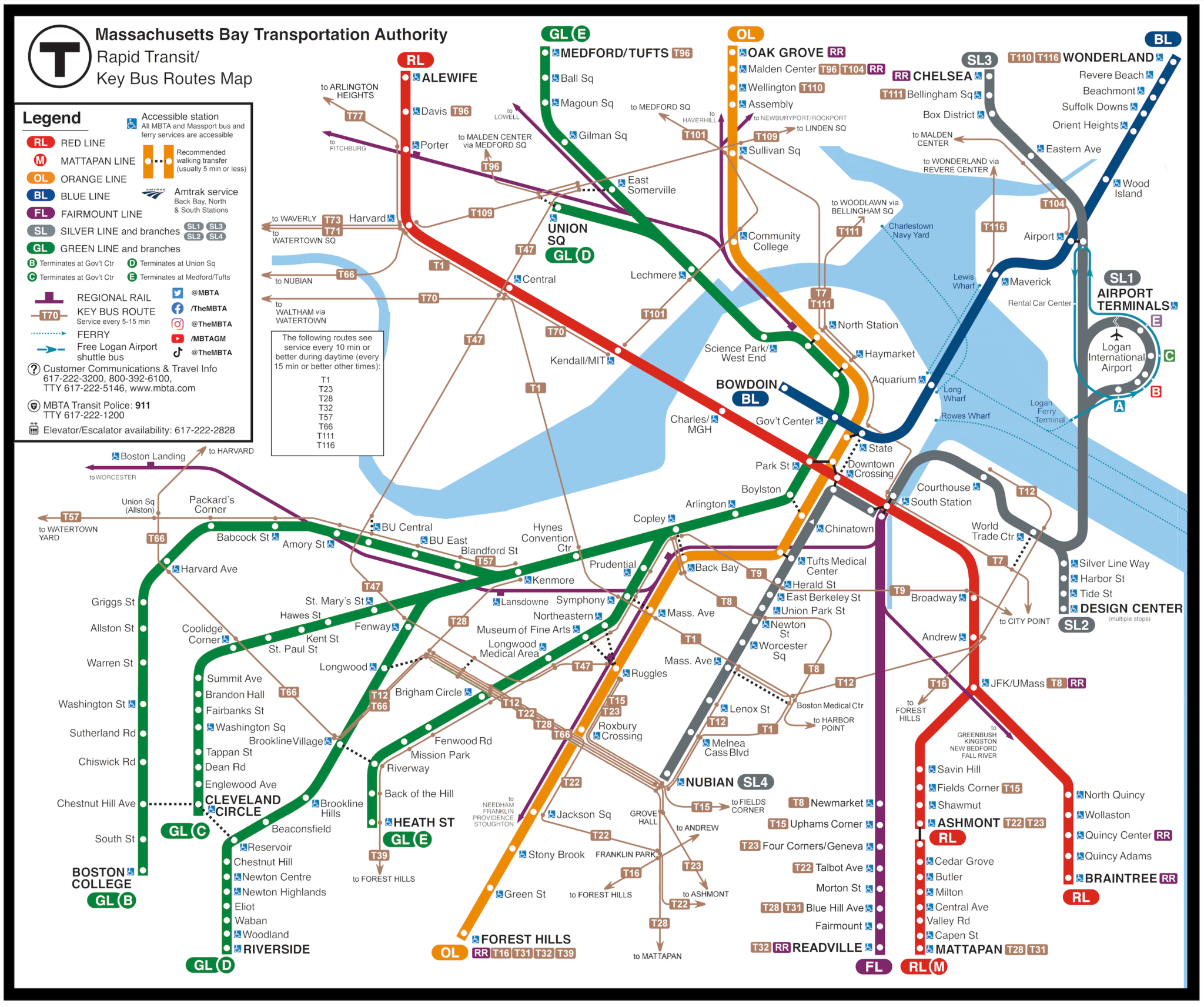

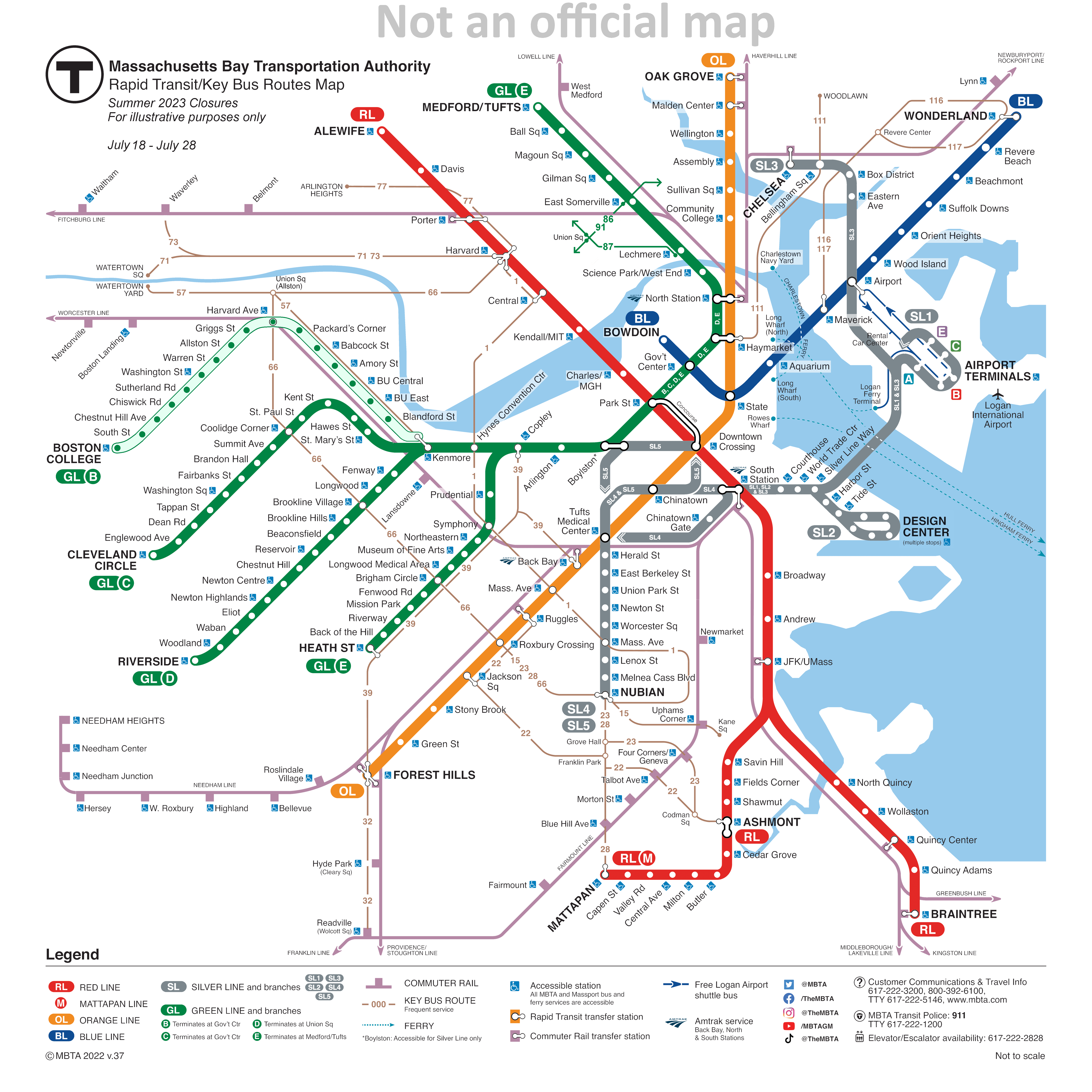

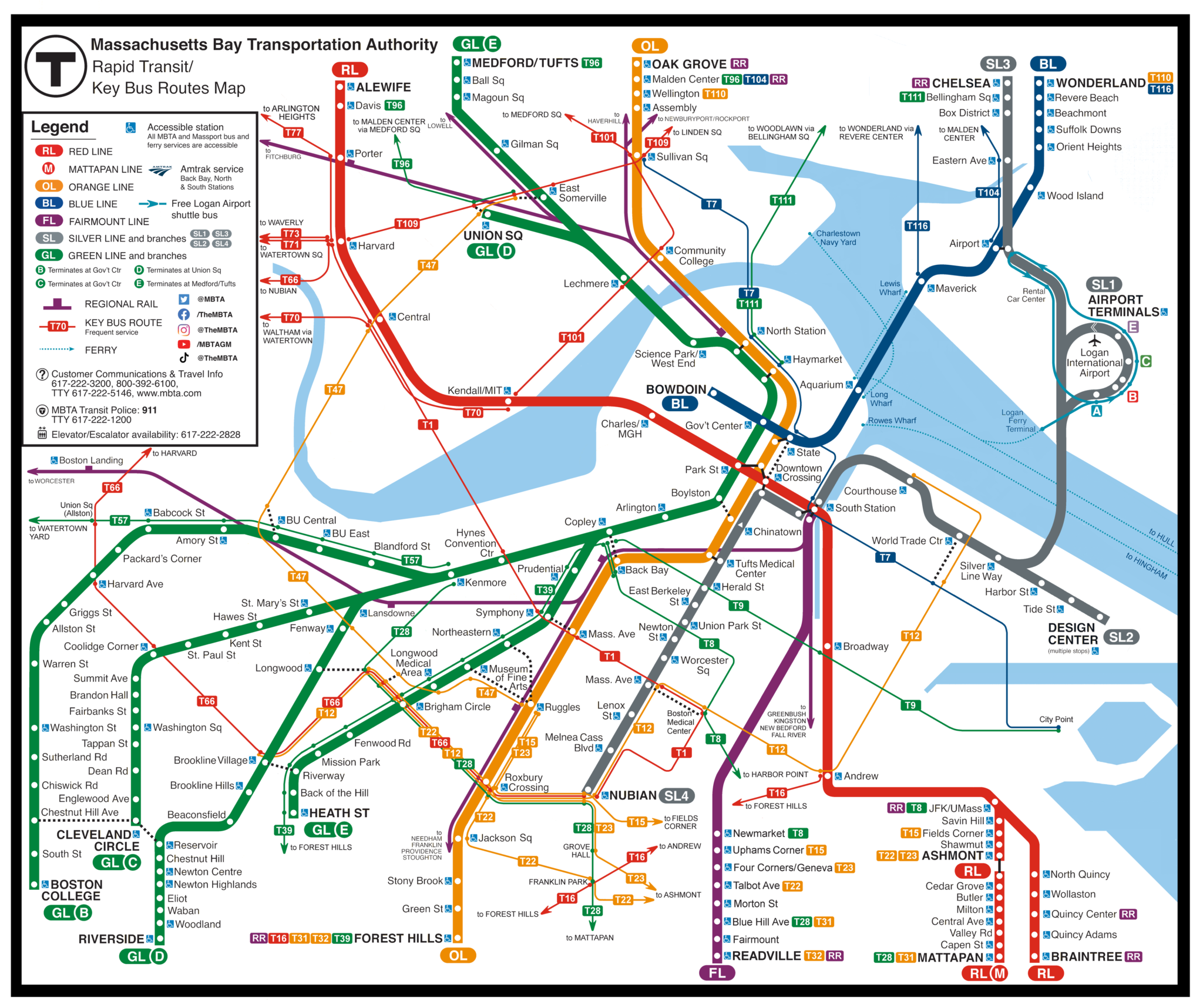

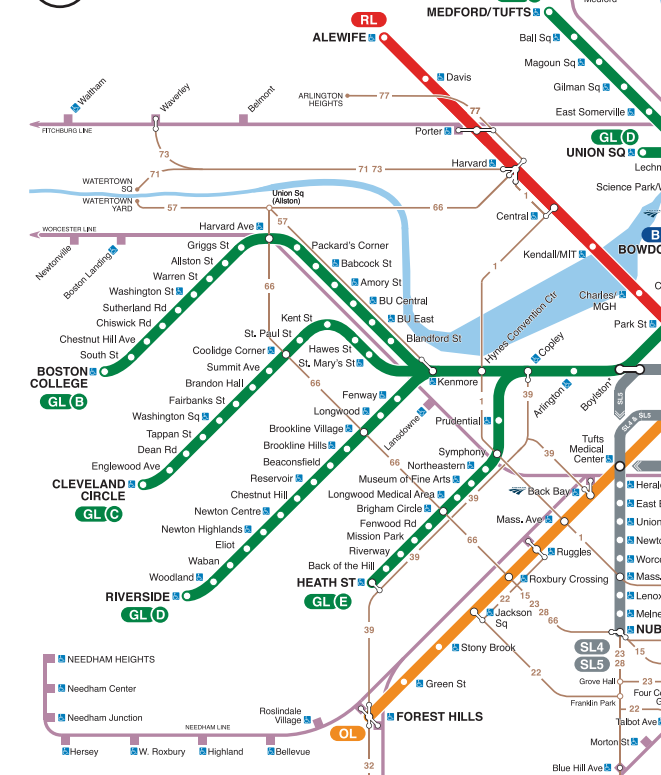

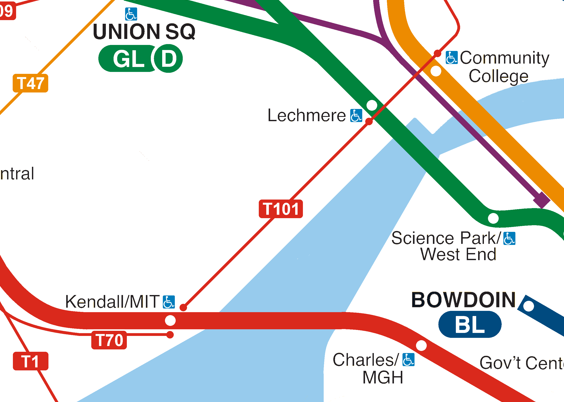

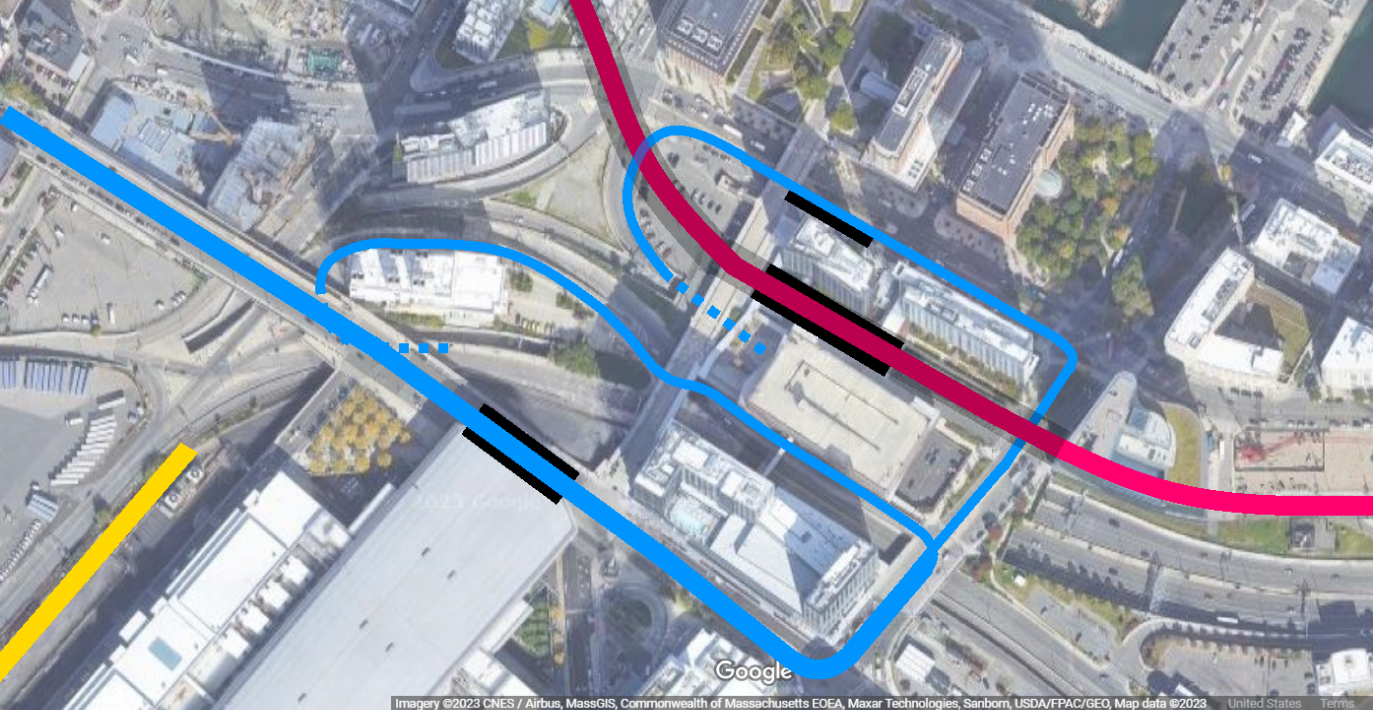

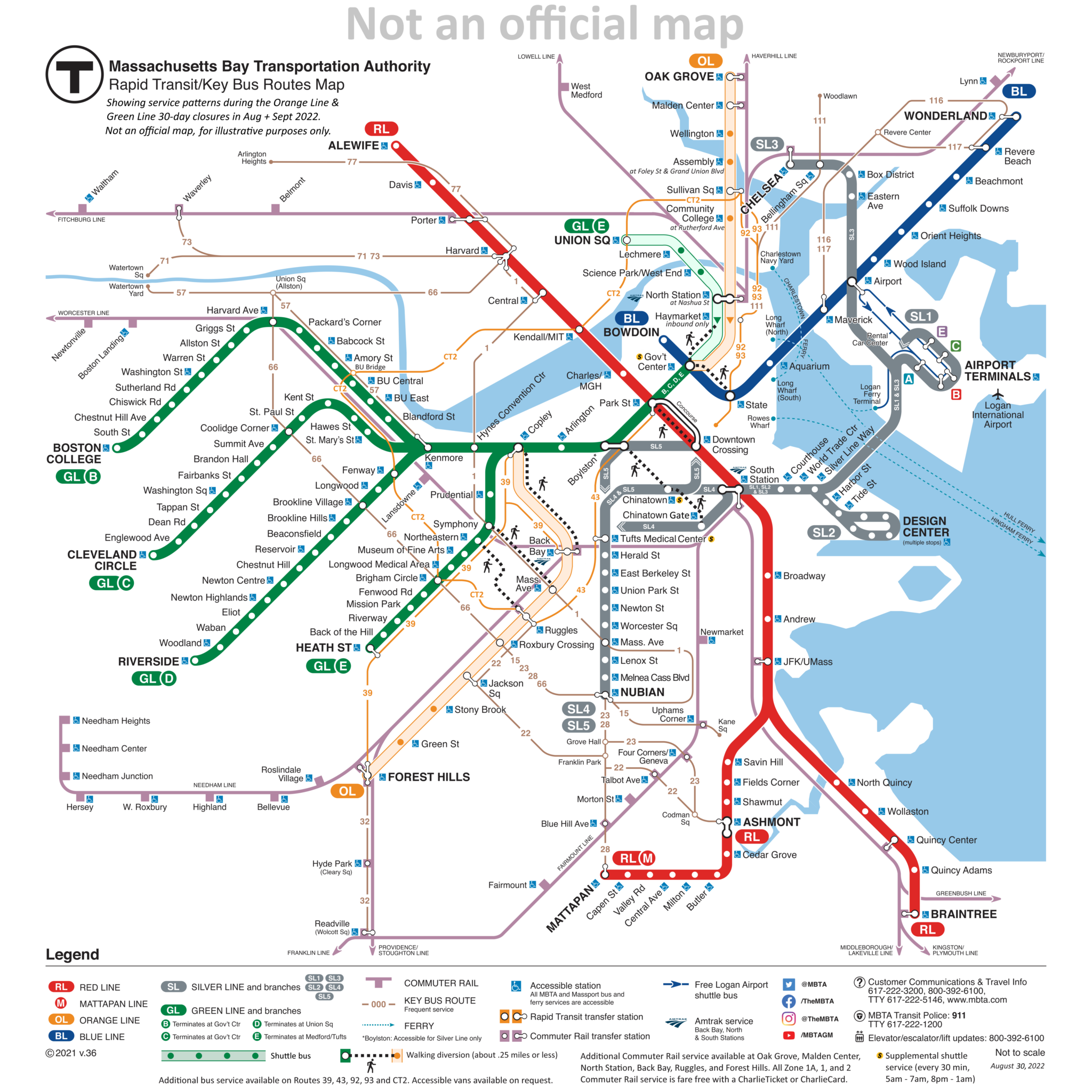

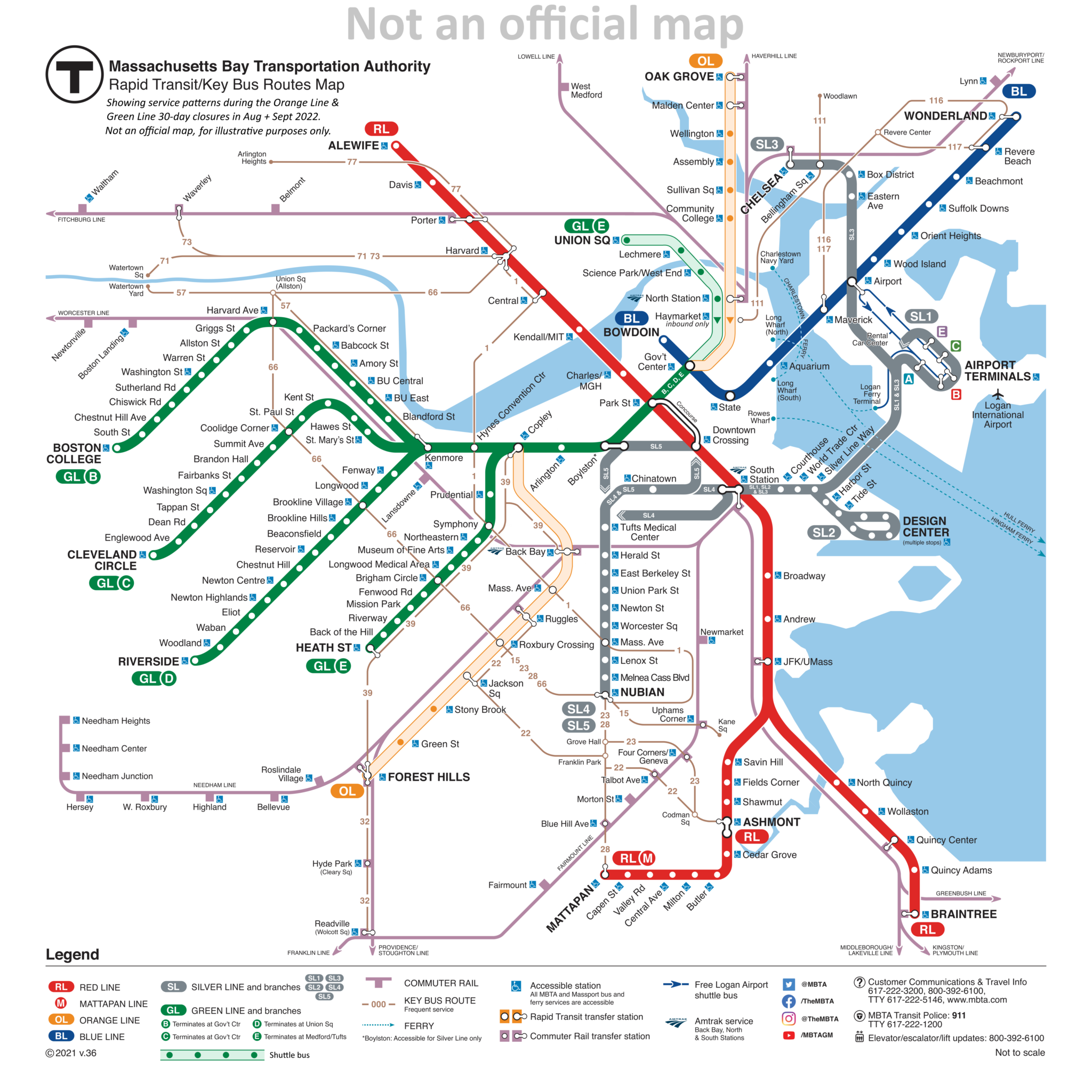

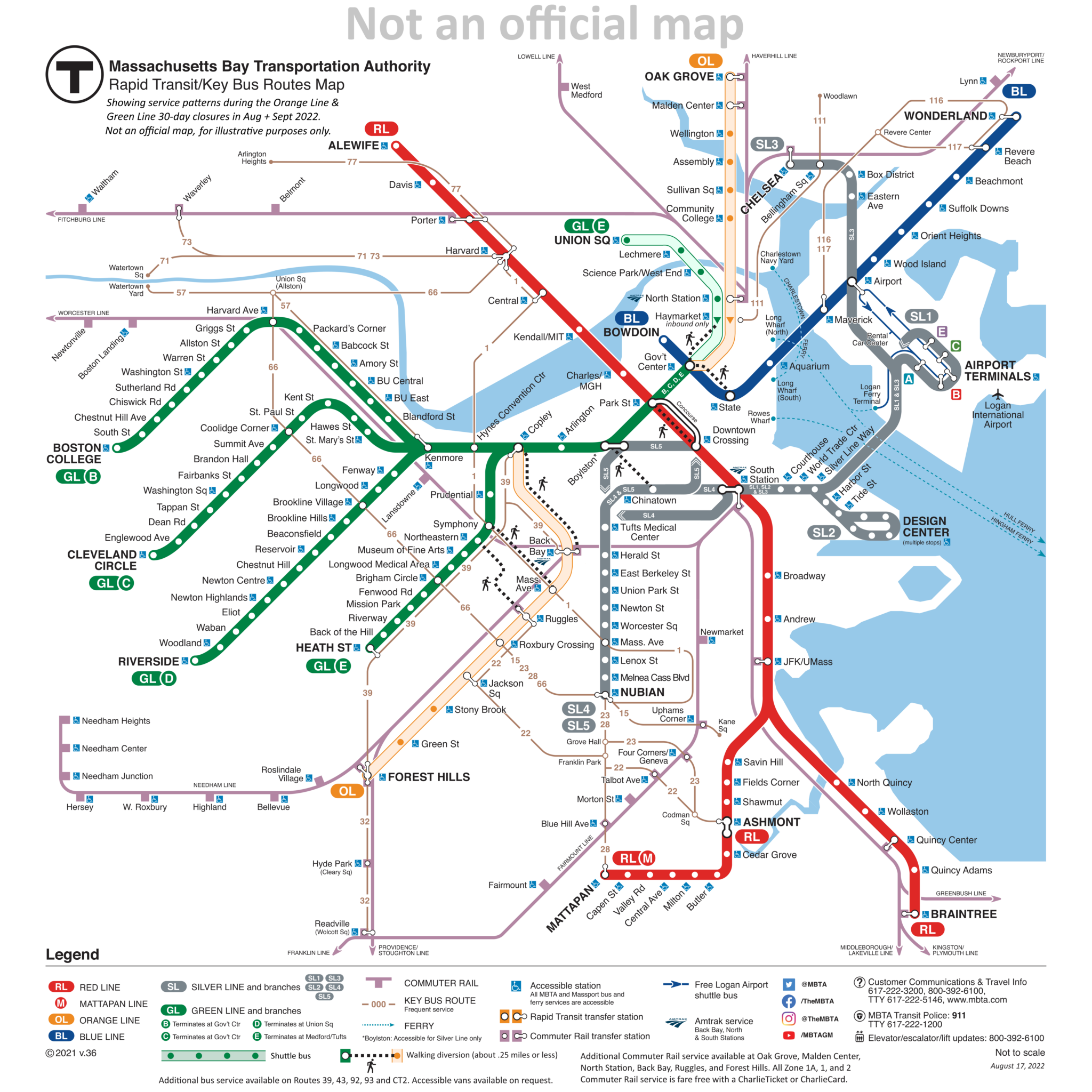

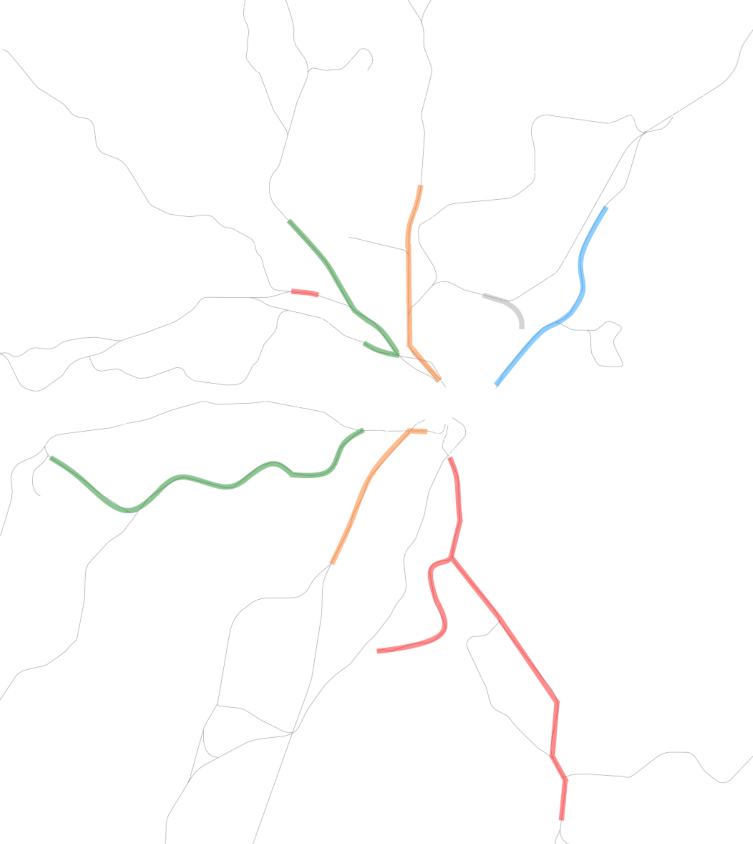

Let’s look at a map of Boston’s railroads (courtesy of Alexander Rapp, links at end of post).

Let’s add highlighting to show the railroad ROWs that are now used by, or shared with, rapid transit.

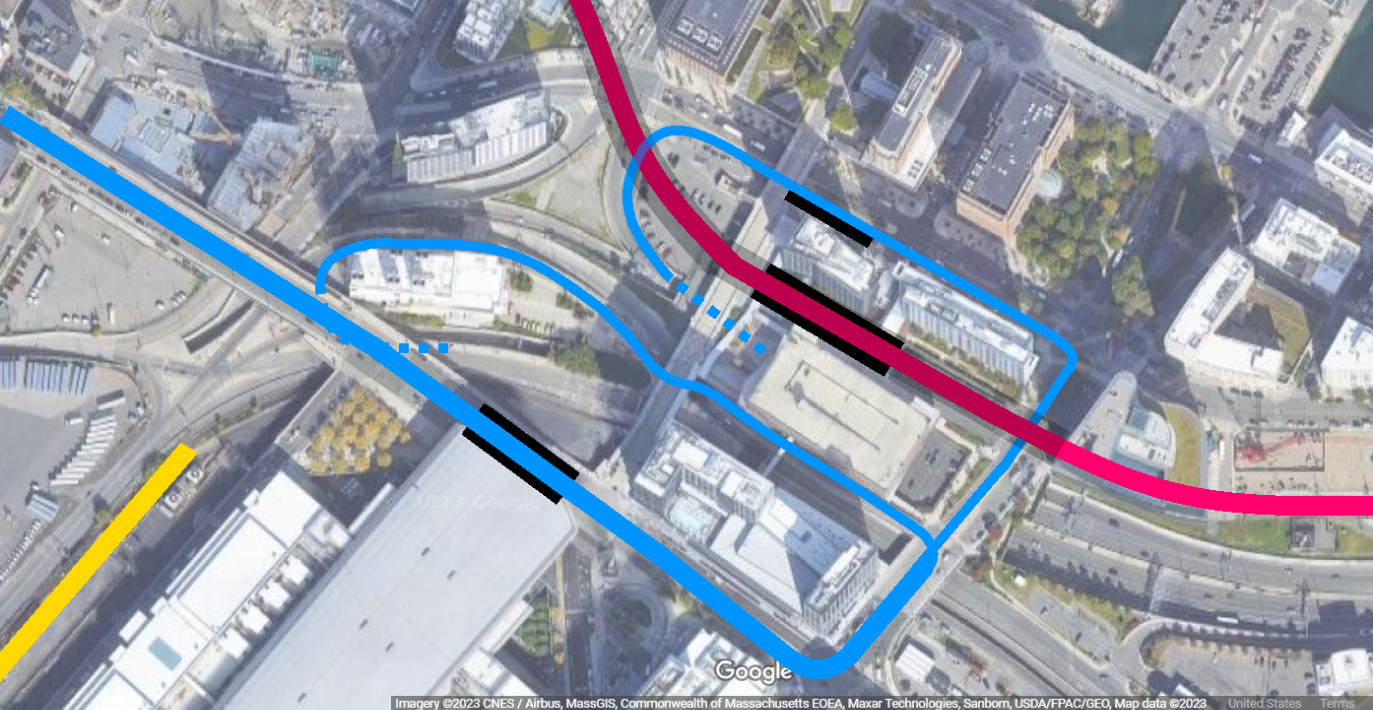

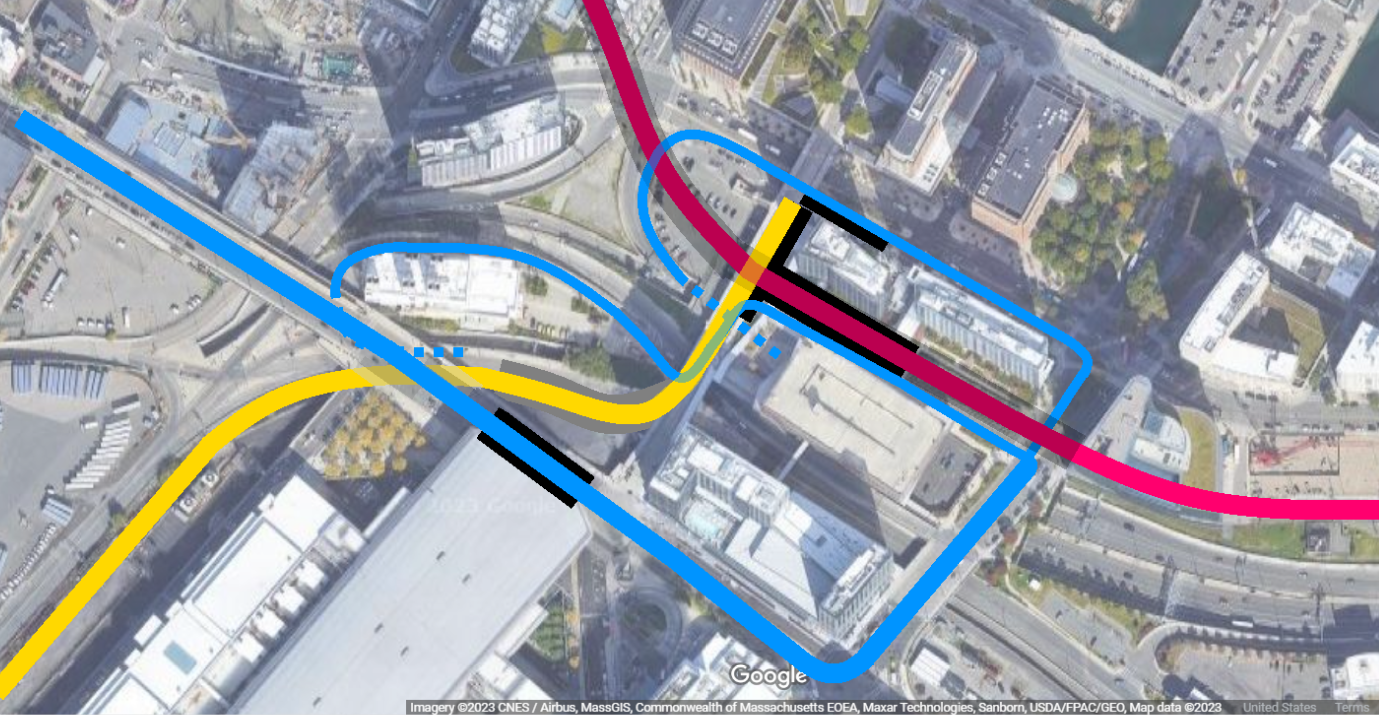

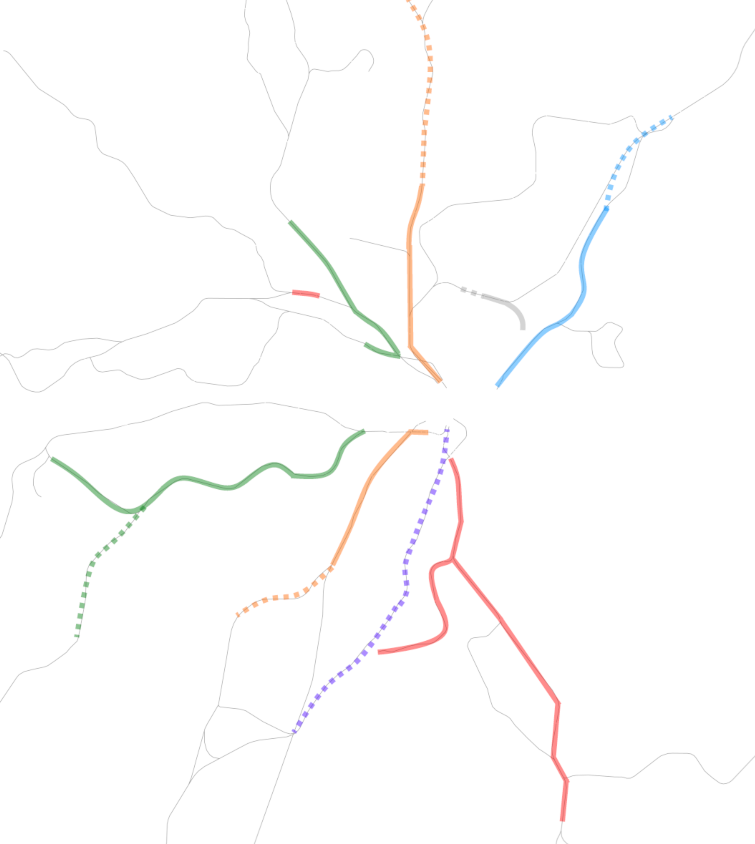

Let’s also add dashed marks to indicate common proposals. Aside from the Red-Blue Connector, most of the SLX alignment, and the North-South Rail Link, all common proposals travel along historical ROWs. (The Union Freight RR doesn’t count.)

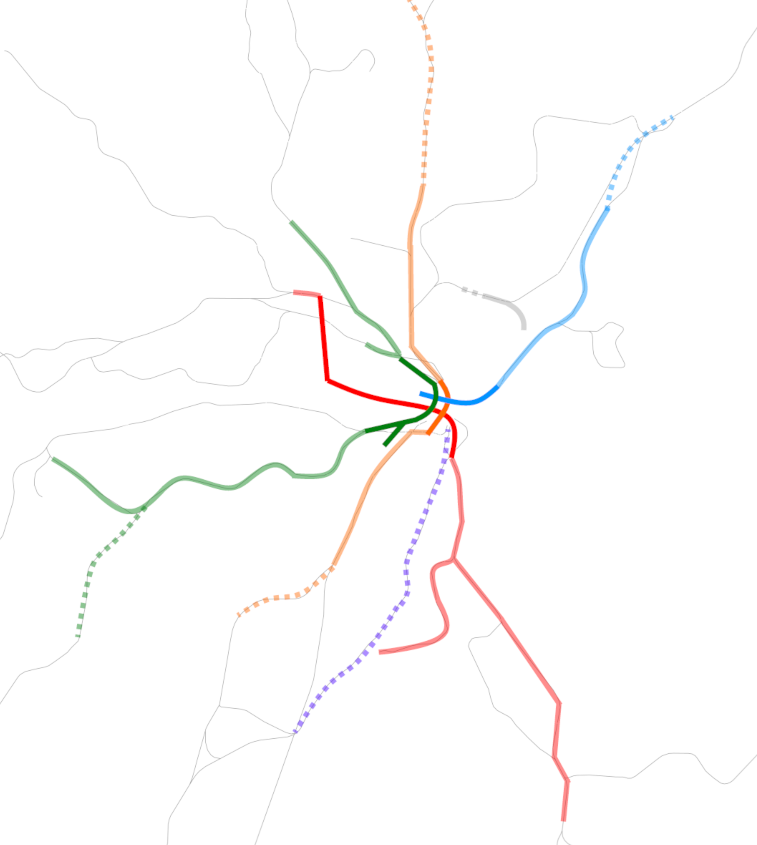

And now let’s also add (imprecisely drawn) solid lines to indicate the new subways that were built across downtown, which now connect historical ROWs on opposite sides of the city. (This reveals that the subway was in fact “the original North South Rail Link”.)

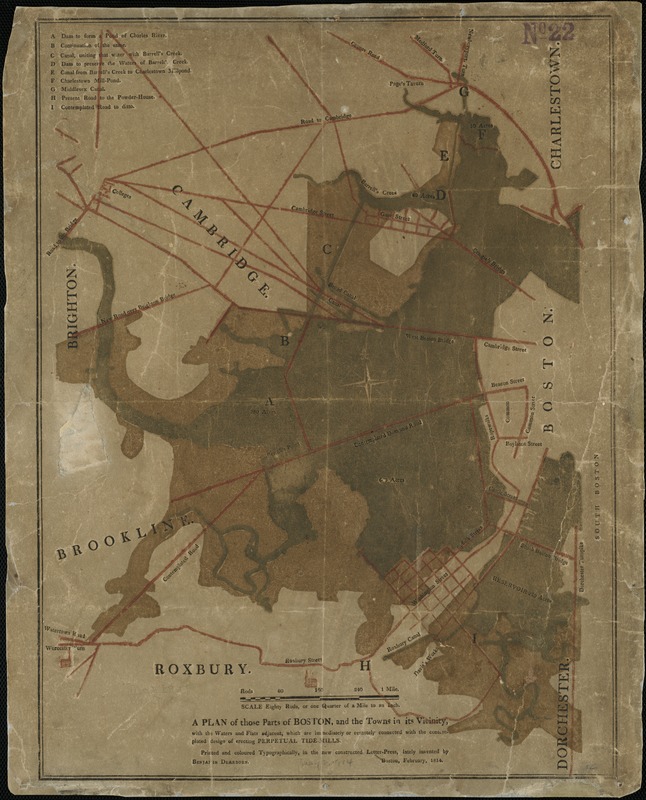

Now, here’s the kicker: the original underlying map showing Boston’s railroads… shows how they looked in 1890.

Which brings us to our first point: the large majority of the T’s (rapid transit) route miles run on the same paths that were carved out before 1890 (many before 1870, and quite a few as early as 1855).

What’s more: many common proposals to expand the T simply reactivate ROWs that were first carved out in the 19th century (in some cases, as much as 170 years ago).

The core of Greater Boston was the exception to this. Like London’s railroads forbidden from entering the City of London, the late 19th century saw railroad terminals circling downtown, with clusters at the sites of today’s North and South Stations, and one terminal near today’s Back Bay. As a result, when rapid transit was first built around the turn of the century, new routes across downtown had to be built from scratch.

But there are three other corridors, outside of downtown, which also needed to be built for the burgeoning network. These three corridors – and why they were needed – still hold lessons for us today. And it comes down to water, wetlands, and peninsulas.

Wetlands and Peninsulas

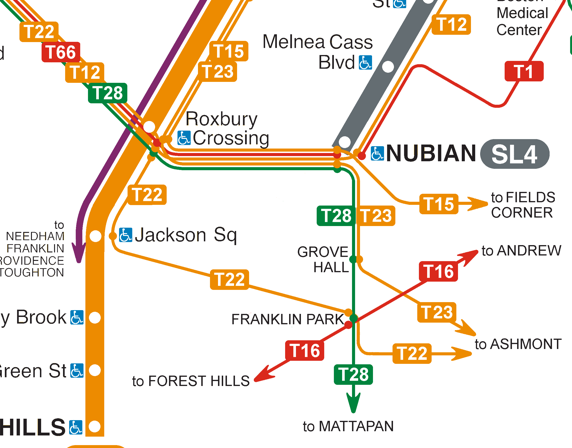

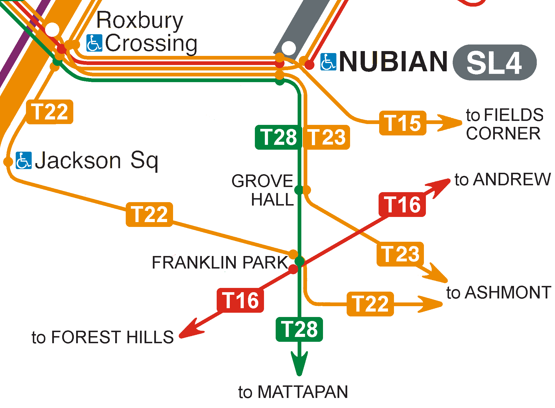

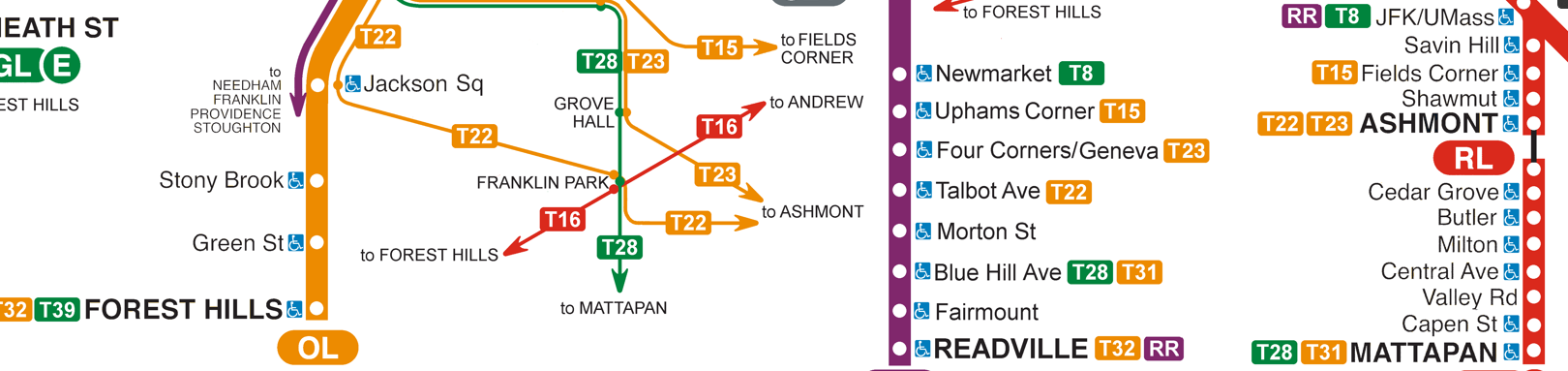

While today’s Orange Line runs along the historical Boston & Providence ROW along the Southwest Corridor, its original route ran down Washington St to what is now Nubian Square, and then further south to Forest Hills. The lack of a historical ROW continues to vex transit designs to Nubian to this day.

So, if so much of today’s network did already exist in 1890, why wasn’t there a railroad ROW to Nubian? A map from 1852 sheds some light:

For much of the 19th century, Boston northwest of Tremont St in what is now the South End… was wetland. (Technically a mudflat.) When the Boston & Providence went to survey the route between their eponymous cities, they opted to build a nearly-straight route on a trestle over the mudflat – entirely bypassing the long-settled Boston Neck, which centered on Washington St from downtown to Nubian Square.

For an intercity railroad, this made a lot of sense. They weren’t in the business of providing local service, and plowing through a long-standing neighborhood in the city would have been costly and complicated.

What is now the Fairmount Line had a similar story. Built by the Norfolk County Railroad as an alternative to the B&P’s route through Back Bay, they opted for a route that reached downtown Boston by way of the South Bay… which, at the time, like Back Bay, was an actual “bay” but also was basically wetlands. Again, the new ROW bypassed the Boston Neck altogether.

And Boston Neck hardly lacked access to downtown. Horsecars and streetcars ran down Washington and Tremont, and Boston Neck held the only route into downtown that did not require a water crossing by bridge or ferry.

By the turn of the century, Boston’s built-up environment had expanded significantly. No longer a bucolic suburb, Dorchester was now indisputedly part of the city. Streetcars trundled on a long slow journey into the center of the city, where they joined streetcars coming in from all across the region. Congestion was extreme and the city needed a way to get streetcars off its downtown streets.

So, a subway was built to send local streetcars from nearby neighborhoods underground, and an elevated was constructed to reimagine the commutes from more distant neighborhoods and suburbs: instead of a single long streetcar ride, commuters would make a short streetcar trip to a transfer station, and then take an express rapid transit train into downtown.

The El running south of downtown traveled directly down Washington St, the heart of the historic settlements on Boston Neck. Unlike the steam railroads’ avoidance of the neighborhood, the elevated railroad was designed to be woven into the expanding cityscape.

The rest is an ironic history. Arguably because it was among the oldest part of the city, Boston Neck never received the kind of railroad ROW which, by the end of the 20th century, was essentially the only place rail transit was allowed to run.

The wetlands surrounding Boston Neck were easier to go through than the neighborhood itself, which doomed the neighborhood to miss out on the “transit land grab” of the 19th century, which continues to govern the location of rapid transit to this day.

Water – Rivers

Rivers divide and unite cities. They split cities into left banks and right banks, and they simultaneously attract settlement to their shores as urban centers of gravity. The city of Boston-Cambridge is no different.

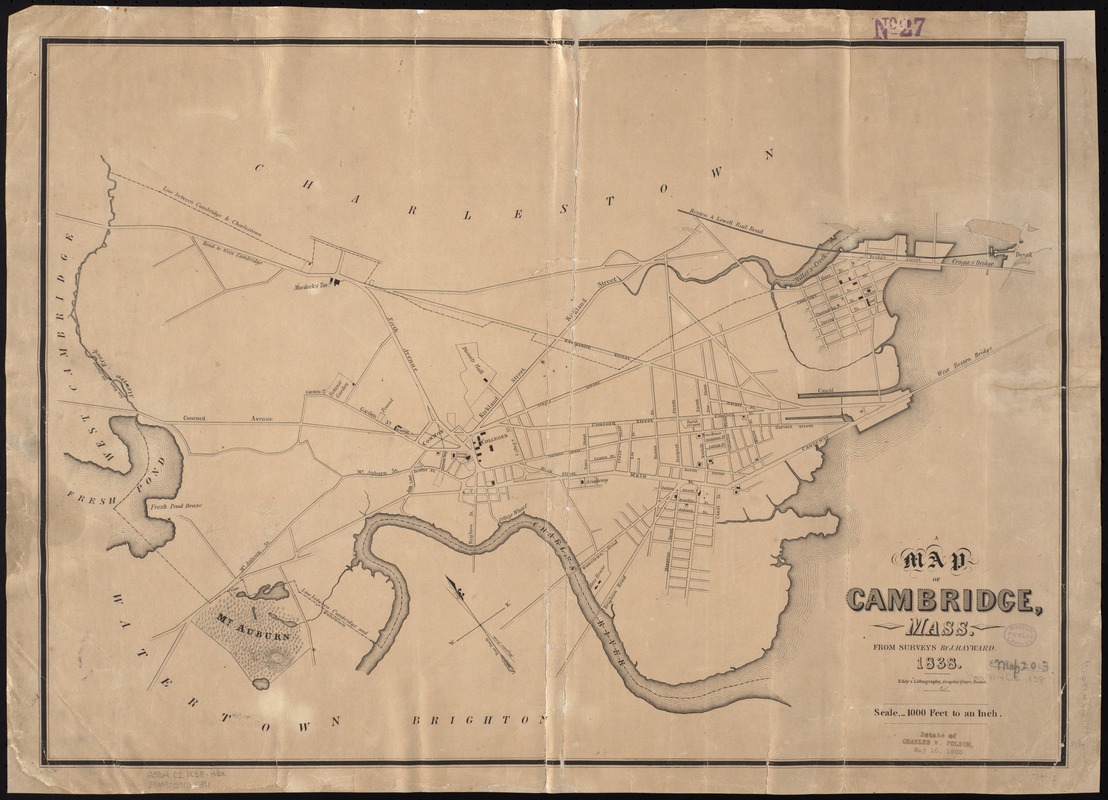

In their earliest days, the cores of Cambridge and Boston/Charlestown sat about 3 miles apart as the crow flies, with Boston/Charlestown sitting at the mouth of the Charles as it empties into Boston Harbor, and Cambridge (its earliest village located in Harvard Square) located about 4 miles upriver. By road, it was a circuitous journey of 8 miles via Boston Neck, Roxbury, and Brookline (along a route likely similar to today’s Silver Line and 66 buses) to cross between them.

A bit more than 150 years after their founding, the effective distance between Boston and Cambridge was cut in half by the construction of the West Boston Bridge (where the Longfellow Bridge is today) in 1792.

In the ensuing hundred years, Cambridge’s center of gravity drifted closer and closer to Boston, as main thoroughfares stretched from the West Boston Bridge straightaway across to Harvard Square.

Broadway (originally a turnpike), Harvard St, and today’s Main St and Mass Ave ran in parallel between the two poles of Old Cambridge and Boston, forming the backbone of the city that would eventually develop along their roughly east-west axes. Cambridge St connected East Cambridge to the rest of the town, and gradual land reclamation filled in Cambridgeport and expanded East Cambridge, bringing the edge of Cambridge’s shores literally closer to Boston.

The Charles River, in its meandering, deposited Old Boston and Old Cambridge a mere three miles apart. The settlements were far enough apart to develop separately, but close enough that they were inevitably drawn toward each other. Boston was anchored by the Harbor and could not move, but Cambridge had plenty of open space to expand into. The opening of the West Boston Bridge created a focal point for Cambridge’s expansion.

The combination of the new river crossing and the original location of the settlement at Harvard Square effectively ensured Cambridge’s development stretching west from downtown Boston.

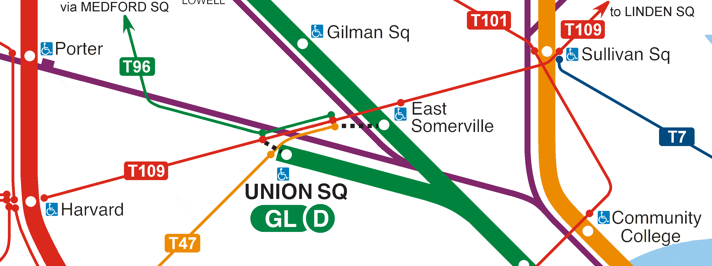

Notably absent, once again, were the railroads. A mid-century short-lived branchline to Harvard Square lasted a mere six years. Cambridge’s expansion was instead fueled by its horsecar and streetcar connections to Boston via the bridges. (Indeed, the first horsecars in the region ran across the bridge, from Bowdoin Sq to Harvard Sq.)

Municipal boundaries notwithstanding, Cambridge became indisputably part of the Boston-Cambridge city, just as Dorchester had. And just like Dorchester, its streetcars were choking Downtown. Dorchester got an elevated railway, and while an elevated was also considered for Cambridge, eventually a subway was chosen instead – a fateful stroke of luck that continues to impact transit access inequity to this day.

Just as the geography of the Boston Neck did, the opening of the West Boston Bridge meant that, by the time railroads started being built, the corridor between downtown Boston and Harvard Square was already well-settled. The railroads had incentive to avoid the area, not serve it.

The dual examples of Cambridge and Boston Neck demonstrate that the construction of railroad ROWs has frozen in time the idiosyncratic mid-19th century divisions between “old” and “new” settlements.

A note on South Boston and the South Bay

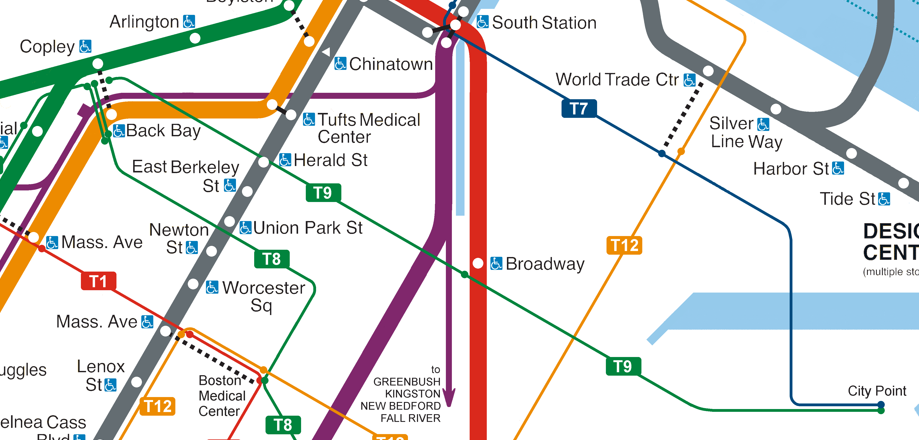

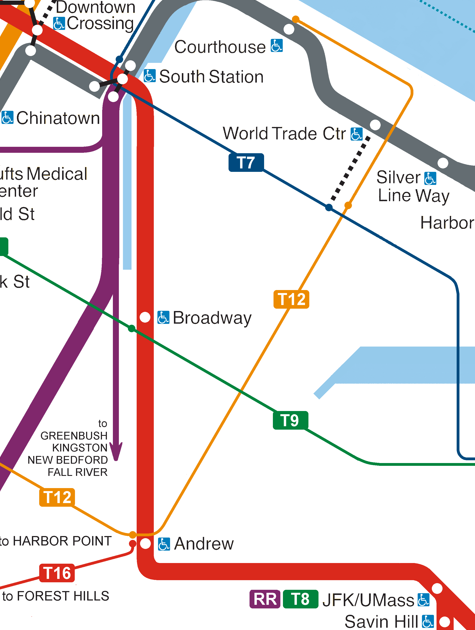

I exclude the southern half of the Red Line from my set of corridors that needed to be created to tie the emerging rapid transit network together, beyond merely stringing together railroad ROWs.

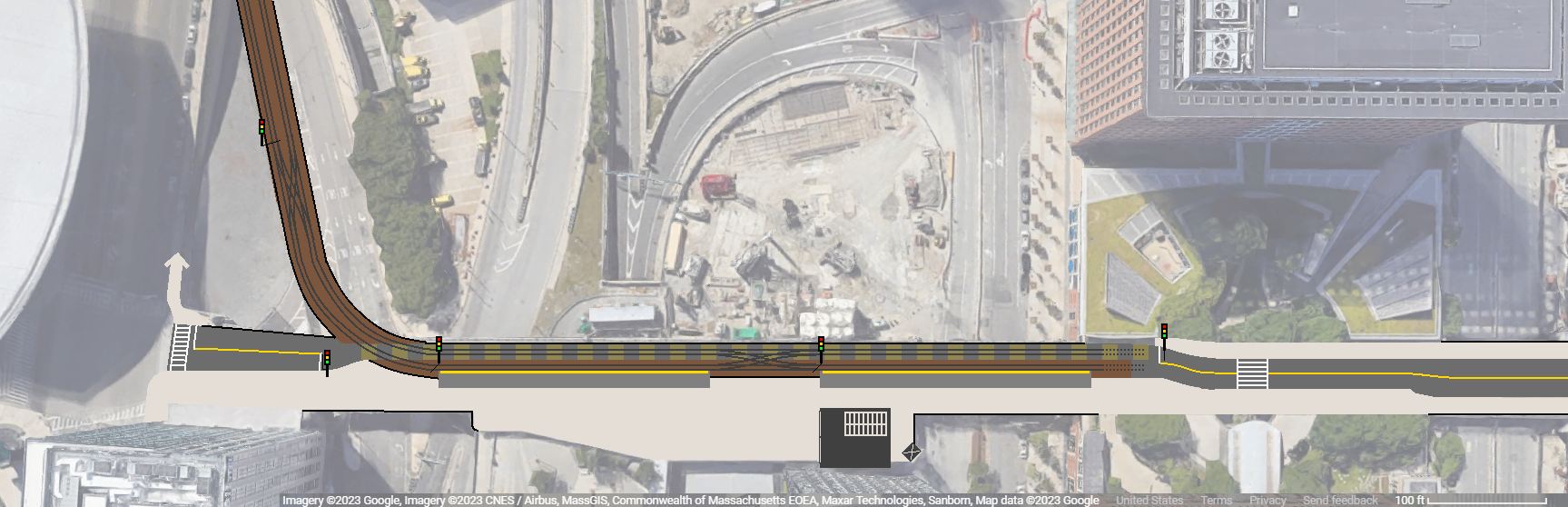

While it is true that the subway between Andrew and South Station was not itself ever a railroad ROW, it runs parallel to the historical Old Colony ROW (which ran in part along what is now Old Colony Ave), and to the historical ROW of the Midland Route (which ran along what is now Track 61 before curving west to a terminal near South Station, producing a route of similar shape, though different location, to today’s Red Line). The decision to run the subway under Dorchester Avenue was not forced by a lack of other options.

The South Bay was, and remains, an odd no-man’s-land separating South Boston from the rest of the city. 150 years ago, water separated the two, and today they are divided by railroad yards and a highway. As such, like Back Bay, it is unsurprising that the Old Colony and Norfolk County Railroads used it as their route in and out of the city.

I argue that the Dorchester Ave subway is essentially a modest relocation and consolidation of these two historical ROWs, and therefore does not represent a “new” taking of land for transit use in the way that the Cambridge Tunnel and the Washington St El did.

(To put it another way, in some alternate history, BERy used either/both of the ROWs in lieu of the Dorchester Ave subway, producing a Red Line very similar to our real one.)

South Boston provides a third example to support the pattern demonstrated by Cambridge and Boston Neck: areas already-settled by the mid-19th century were bypassed by the new railroad ROWs that now serve as our primary space for transit. The Old Colony RR built their ROW along the edge of Southie, just as they built their Dorchester ROW along the edge of the neighborhood hugging the shoreline.

Water – Harbors

The last piece of today’s MBTA rapid transit system that was not built on land set aside in the 19th century (see below) is the East Boston Tunnel, crossing the waters of Boston Harbor.

(In this piece, I don’t discuss the Green Line’s development, as I’ve covered that elsewhere — see links above. I will note, however, that the B and C’s reservations on Beacon and Commonwealth both also date from the 19th century. The vast majority of our dedicated transit land comes from this era.)

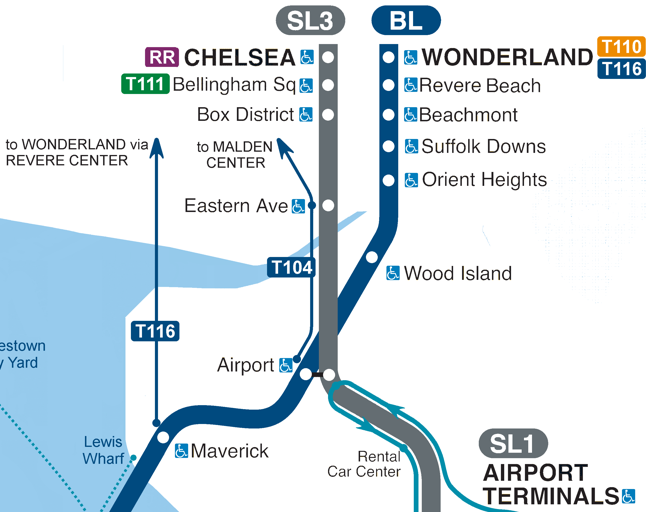

There’s an argument to make that the East Boston Tunnel was, in fact, set aside by private railroads in the 19th century. The Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad ran from the wharves of East Boston to Lynn along what is today the Blue Line. The railroad was enormously successful, running high frequency electric trains with (I believe) near-24 hour service at some points. The “last mile” of the journey was completed by ferry across the Harbor to Rowes Wharf (likely the reason for BERy’s construction of an el station there).

Given the close connection between the rail service and the ferry service, there’s an argument to make that the cross-Harbor corridor was, in fact, “claimed” by a private railroad in the 19th century, just as I argue most of the T’s current network was.

The popularity of the BRB&L, and the 1924 conversion of BERy’s East Boston Tunnel to heavy rail, speaks to the importance of a Boston Harbor Crossing. East Boston itself, originally an island, remained isolated from the mainland by Chelsea Creek. And Revere, though served by the B&M’s Eastern Route (today’s Newburyport/Rockport Line), was much more directly served by the near-direct 4.5 mile corridor via East Boston, compared to the 7 miles via Chelsea.

Crossing Boston Harbor has a similar effect to crossing the Charles River – providing an alternative to the roundabout route (whether via Brookline or Chelsea or via an unreliable ferry) creates a strong focal point at the crossing, drawing the previously remote far shore closer (both metaphorically and sometimes literally).

(Off-topic but I always want to emphasize this: the BRB&L ran rapid-transit-like service to Lynn until 1940; only eight years later, the MTA began construction of a true rapid transit line along that ROW, intended to once again reach Lynn. The first phase opened in 1952, and the second phase, to Wonderland, opened in 1954, truncated short of Lynn for budgetary and political reasons. There was only an eight year gap in service before public plans were made to restore service to Revere and Lynn, and Revere’s service was restored a mere four years after that. We shouldn’t talk about extending the Blue Line to Lynn – we should talk about restoring the Blue Line to Lynn.)

Like the rapid transit lines across Boston Neck and Cambridge, a rapid transit line across Boston Harbor was needed precisely because it had been too expensive and unappealing for a private intercity railroad company to build the ROW.

And that’s where the rubber hits the road on this topic, even today.

Implications

Most of the MBTA is built along corridors where for-profit railroads found it advantageous to build in the mid-19th century, usually through areas that were lightly settled, avoiding the historical cores that had driven the growth of the region until that point.

Setting aside the Green Line, there are four exceptions to this pattern:

Downtown: where the Main Line’s Washington St Subway provided the “original North-South Rail Link”

Boston Neck: where the El ran above one of Boston’s earliest pieces of land, to serve the large streetcar suburbs in Dorchester beyond, in the 1.6 mile gap between the Boston & Providence RR and the Norfolk County RR’s Midland Route – the largest gap between railroad lines in Boston’s immediate suburbs, except for the gap in Cambridge

Cambridge: where the subway ran along an east-west axis that had been rapidly settled starting at the dawn of the century, filling a 2 mile gap between the B&A’s railroad in Allston and the Fitchburg Railroad’s line in Somerville

Boston Harbor: where a tunnel literally was dug under the ocean to clear a 3,000 foot gap, replacing the choice between an unreliable ferry and a detour of 4 miles (or more)

Among other things, this highlights – yet again – how damaging the loss of a radial line to Nubian is. Imagine if the Red Line had been relocated out of its tunnel to a route along the B&A ROW with a Ruggles-like transfer station near Braves Field, or along the Fitchburg ROW, with a transfer station at Union Square.

I believe this demonstrates that a transit approach that limits itself to existing transit ROWs threatens to overlook corridors that could be as vital in the 21st century as the above corridors were in the 20th.

The map at the beginning of this post is from Alexander Rapp’s utterly delightful timeline of transit routes in Greater Boston by mode, modified to show just the steam/diesel train routes.