“Wait”, you say, “that’s not right. The Green Line turned 100 in 1997, with the centennial of the Tremont Street Subway’s opening.”

True enough. But the Tremont Street Subway, for its first quarter-century of operation, looked quite different from the modern Green Line. It was only in the early 1920s that it began to resemble the system we know today, and it was only in 1922 – not 1897 – that the modern Green Line was born.

An Underground Street

BERy (the Boston Elevated Railway Company, the MBTA’s primary private predecessor) saw the tunnel more like a substitute for the crowded street above than as a proper rapid transit subway.

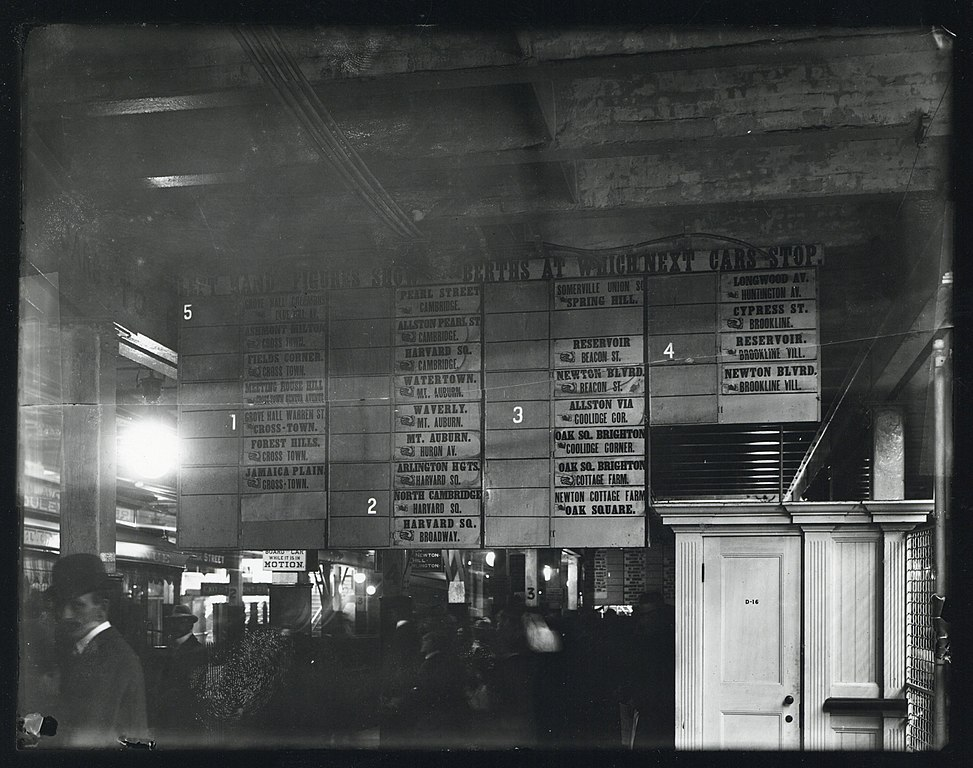

Streetcars funneled in from all over the city and distant suburbs, squeezing into the subway and crawling along at the speed of a modern bicycle. Contemporary accounts describe crowds surging down the platform at Park Street when the boarding location of the next trolley to such-and-such suburb was announced. The destination board at Park Street in 1899 resembles a departure board at a mainline station like South Station or Grand Central much more than that of a rapid transit station:

The streetcar subways draw a clear contrast with the services which BERy did consider rapid transit (the predecessors to today’s Red and Orange Lines). Beyond the difference in rolling stock (high-platform third rail vs low-platform wired), the rapid transit lines were also distinguished by their use of transfer stations.

A Tale of Two Transit Trips

Compare these two rider experiences:

- A commuter from Somerville boards a trolley at the intersection Highland Avenue and Willow Avenue.

- The car trundles down Highland, stopping every couple of blocks to pick up passengers.

- After 2.7 miles, the car reaches Lechmere Square…

- …where it departs from the street and enters the streetcar-only Lechmere Viaduct…

- …which snakes over the Charles and around the West End before…

- …diving into the subway just north of Haymarket.

- After another 1.5 miles, the commuter disembarks at Scollay Square

Vs.

- A commuter from Dorchester boards a trolley at the intersection of Blue Hill Avenue and Seaver Street (equidistant from downtown to the Highland/Willow intersection in Somerville).

- They actually have a choice of trolleys – bound for Egleston, or bound for Dudley (now Nubian).

- They travel by streetcar for 1 to 1.7 miles, stopping every couple of blocks to pick up passengers,

- before arriving at their rapid transit station where they get a (free) transfer to the Elevated.

- The Elevated speeds into downtown, with stops roughly every three-quarters of a mile.

- The commuter disembarks at State Street.

The Somerville commuter takes a long slow ride from the suburb to the core, while the Dorchester commuter takes a short slow ride followed by a short fast ride, enabled by a transfer station.

A Tunnel Filled With Buses

For BERy, in those first 25 years, the Tremont Street and Boylston Street Subways were just ways of getting the huge volumes of streetcars off of the streets in downtown. In today’s terms, those tunnels were essentially filled with buses. This was useful transit service, to be sure, but it wasn’t rapid transit.

The same was true of the East Boston Tunnel. Extended from its Court Street terminus in 1916 to a portal on Cambridge Street (with a turnback loop at Bowdoin, still used today), the tunnel’s primary use was to bring East Boston trolleys under the Harbor into downtown. In fact, early in the planning of the East Boston Tunnel, one option that was considered was to have trolleys exit the tunnel from Maverick through a portal in the North End, and continue on street-level into downtown – similar to today’s Sumner & Callahan Tunnels. The primary use of the tunnel was to get trolleys (or “buses”, if you will) under the harbor – not to create rapid transit service.

In the early 1920s, that all began to change.

Conversion to Rapid Transit

Birth of the Blue Line

The 1924 conversion of the East Boston Tunnel to rapid transit is well-known and offers a clear example of how a streetcar tunnel can be transformed into a rapid transit subway. The vestigial surface route on Cambridge St was converted to bus, and the half-dozen streetcar routes to the east were cut back to terminate at a new transfer station at Maverick. Thereafter the local streetcar services fed into a dedicated rapid transit service, mirroring similar designs at Dudley, Harvard, Sullivan, and others.

This, I would argue, marked the birth of the modern Blue Line; while it is true that today’s State (f.k.a. Devonshire) and Aquarium (Atlantic) stations opened some 20 years prior, it was only with the 1924 conversion that the service became anything like its modern form.

(There’s also an argument to be made that the true birth of the modern Blue Line actually occurred a bit further to the east, during the early and highly successful years of the Boston, Revere Beach & Lynn Railroad, which was essentially running Indigo Line-style service 100 years before its time.)

As a matter of comparison: mainline rail service with today’s rapid transit stop spacing had been running along both the Highland Branch and what is now the Southwest Corridor for 70 years and 100 years respectively before their conversion to rapid transit; but I don’t think we would say that either the modern Green Line or Orange Line were born circa 1888. We would consider those to be predecessor services, and I would argue that we should view the streetcars in the East Boston Tunnel as a similar predecessor service (albeit of a different character).

Birth of the Green Line

Less well-noticed – but I would argue equally important – was the 1922 construction of the transfer station at Lechmere. Like at Maverick, local streetcars were now short-turned at a rapid transit station where passengers transferred to service that was dedicated to bringing riders downtown at high speed.

In fact, in those early years, BERy ran a dedicated service to Lechmere for this purpose; a “shuttle” service ran from Lechmere to the Pleasant Street Portal for the first six months, which was rerouted to Kenmore in early 1923. Note the similarity to the East Boston Tunnel’s rapid transit service – “shuttle” services whose sole purpose is to run between downtown and a transfer station. More information in a contemporary newspaper account here.

Over the following ten years, BERy experimented with extending Lechmere service on to the Commonwealth and Beacon branches, which eventually both through-ran to Lechmere until the early 1960s. With their dedicated medians, the Commonwealth and Beacon branches were indeed the most “rapid-transit”-like of the various services feeding into the Central Subway at the time. They still intermingled with “local bus”-like services to Watertown, Huntington, Egleston, Dudley, City Point, and Sullivan, but the clear intent was to create a “rapid transit” service, as much as possible.

The efforts to replicate the success of the “rapid transit transfer station” model were originally envisioned to go even further. As discussed previously in my Blue Line series, plans were made for another transfer station in Allston, which is why Kenmore station – not constructed until 1933 – was built with a loop for the Beacon line; the hope had been to convert Kenmore into a transfer station for a Beacon streetcar and a Commonwealth rapid transit line, Maverick-style. You can see a 1926 proposal for such a network here:

The construction of the Lechmere transfer station marked the turning point from BERy treating the Tremont Street Subway as a collection of independent streetcar routes into BERy treating the Subway like a trunk line with multiple feeder branches – in short, the modern Green Line.

Death of the Streetcar Network

Following the cutback of the Lechmere services, the once-expansive network of streetcar routes running into the subways (a subject for a later post) started a rapid winnowing in which the same story played out again and again: a transfer station was constructed and the streetcar route was cut back to the transfer; once a route no longer needed to travel into the subway, bustitution almost always quickly followed.

This is one place I want to draw our modern attention to. I’d always thought of bustitution as a phenomenon of the latter 20th century, driven by the post-war embrace of the automobile. In fact, the vast majority of bustitutions happened between 1922 and 1941. If anything, the pace rapidly slowed following the war, and it is in fact remarkable that Arborway survived all the way to 1985.

- 1922: Lechmere Network cut back once transfer station opens

- 1924: East Boston Network cut back once Maverick opens

- 1925: the Ipswich Street Lines (the predecessors to today’s 55, 60, and 65) were truncated at Massachusetts (now Hynes) station

- 1932: the routes along what is now Route 9 to Chestnut Hill were bustituted and redirected to Kenmore’s surface station

- 1935: last year that foreign streetcars from the North Shore ran into the subway, halted by the loss of the bridge over the Mystic River

- 1938: the local streetcar running below the El along Washington St between Dudley and the subway was substituted with a bus (described here)

- 1941: the Huntington Avenue Subway opened, and streetcars stopped using the Public Garden Incline.

At this point, the winnowing slowed significantly, and the system had largely transformed into the modern Green Line we know today, with a few extra branches (to Egleston, City Point, and Charlestown) hanging around.

- Late ‘40s: the two Charlestown branches are eliminated, just barely outliving BERy itself

- 1953: the City Point branch is eliminated by the MTA

- 1956: the Egleston branch is cut back to Lenox Street

- 1959: the Riverside Line is converted to light rail, expanding the MTA’s reach to Route 128

- 1961: the Lenox Street branch (formerly running to Egleston) is cut back to the Pleasant Street Portal, and briefly runs as a shuttle service between Boylston and Pleasant Street

- 1962: the shuttle to Pleasant Street is canceled, and the Pleasant Street Portal – once an anchor of the streetcar subway – falls into disuse

- 1965: through a consulting engagement with Cambridge Seven Associates, the newly incorporated MBTA assigns colors to its rapid transit lines for the first time – the literal origin of the term “Green Line” (as well as the birth of the iconic spider map)

- 1969: the “A Line” – having survived long enough to actually be called “the Green Line” – is eliminated

And in this context, we now see that Arborway’s survival all the way to 1985 almost seems improbable by comparison – the last in a 60-year effort to remove all streetcars from the subway.

The cruel irony is that this effort – originally intended to speed up service and improve reliability in the subway – contributed to an overall degradation of transit access in the region over the following century. Once streetcar routes were taken out of the subway, they were very easy to replace with buses, and once they were replaced with buses, it was very easy to quietly degrade or eliminate service.

Conclusion: 100 years of the Green Line

In writing this, I read a lot of old reports written about Boston transit in the early twentieth century. One thing that struck me is that the reports written in the 1920s have much more in common – in terms of priorities and perspectives – with today’s approaches than they do with the reports written by their predecessors a mere 30 years beforehand.

By the 1920s, recognition had set in that the streetcar subways could and should be converted into rapid transit, using the same transfer hub model that had been successfully deployed at Sullivan, Dudley and Harvard.

(Interestingly enough, it had also become clear by this point that those elevated railways – built barely twenty years earlier – were awful and needed to be replaced as soon as possible; both the Southwest Corridor alignment and the current Haymarket North alignment to Sullivan were explicitly described in the 1926 report.)

The 1922 opening of the new Lechmere transfer station marked this pivot point, after which every single capital exercise carried out on the streetcar network was done with the aim of turning the subway service into a rapid transit service – or getting it as close as possible.

This continues to this day! The Green Line Extension project is undeniably a rapid transit project, and not just a resurrection of the former Lechmere streetcar network, and the same will be true if the Green Line is ever extended to Needham. Moreover, it seems all but certain that a Green Line extension to Nubian Square would need to find ways to make itself as “rapid transit”-like as possible – or else face a century of institutional inertia to overcome.

The notion of a “Green Line” with branches feeding into a trunk – as opposed to an urban streetcar network whose density called for a tunnel in key locations – arose in the early 1920s. Today’s Green Line is much more closely related to the LRT subway service of the 1920s than of the 1900s, in structure, operation, and public branding. It arises out of 1920s ideas about hub-and-feeder networks, which had previously been applied on other routes, and were then brought to the streetcar networks following their success. The creation of the rapid transit line that would become the Green Line occurred not in 1897, but in 1922.

And so, that is why, this summer I’m celebrating the Green Line’s (true) 100th birthday.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to a host of transit historians, who have produced reams of carefully researched accounts detailing the stories of Boston’s transit system over the decades; most of them did so as volunteers, producing labors of love that exemplify the root of the term “amateur”. I want to specifically mention the names of Ron Newman, Bradley Clarke, O.R. Cummings, Frank Cheney, and Anthony Sammarco, as well as the volunteers who maintain the Wikipedia pages on Boston’s transit network.