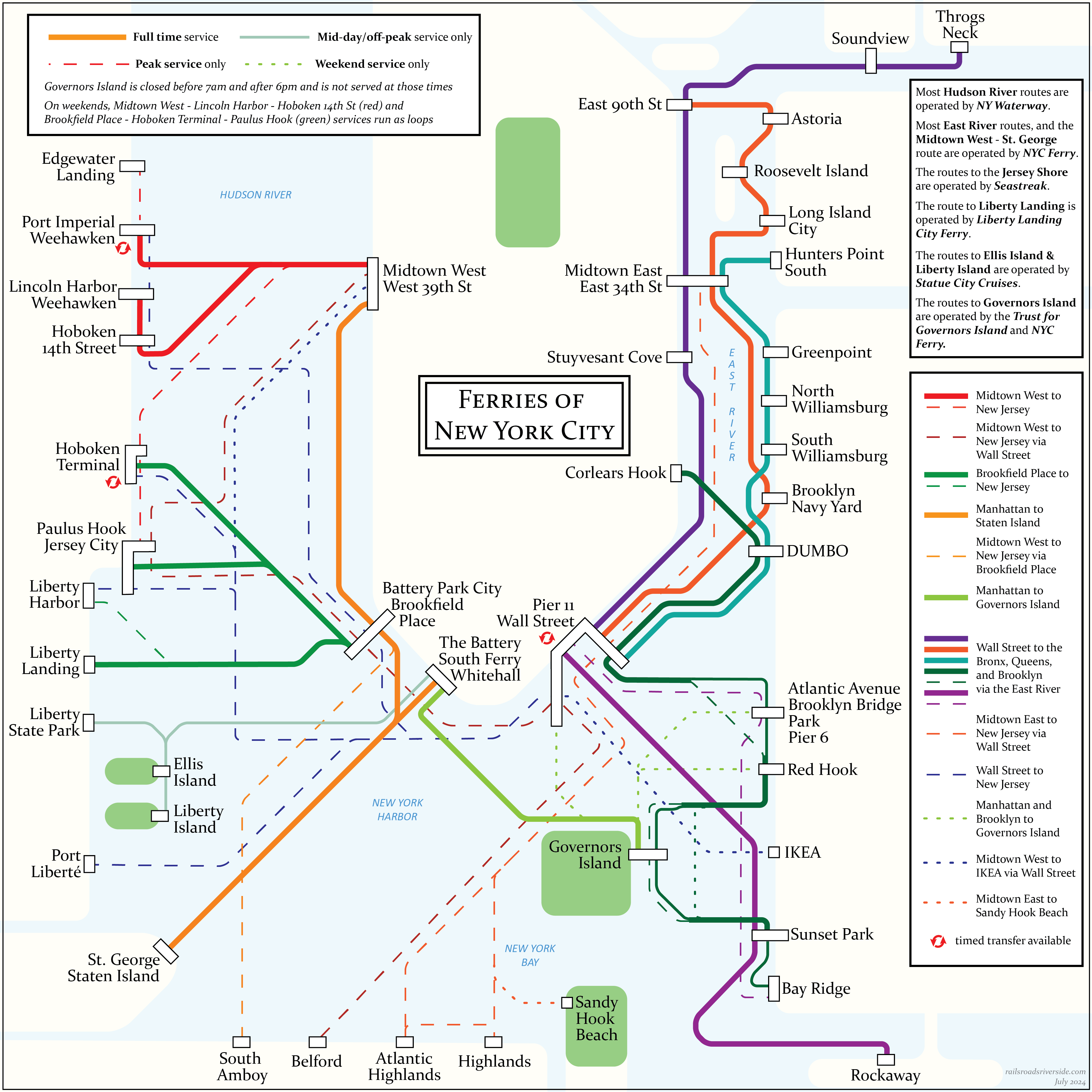

What could be more patriotic than posting a map of New York City ferries? (That comment was unserious, but it belatedly occurs to me that I probably could have cleverly woven in something about the Statue of Liberty. “Fourth of July” -> “Lady Liberty” -> “The ferry that goes to the Statue of Liberty” -> “all the other ferries” -> “here’s a map”, something like that.)

As described in the top right of the map, there are something like half a dozen of companies running commuter and/or full-time ferry services on the waters surrounding New York City. As far as I can tell, no one has made a consolidated map showing all of these services in one place. I suspect this is because there isn’t a huge amount of geographical overlap between the “territories” of the companies.

- NY Waterway operates on the Hudson, with criss-crossing network of peak-only services and a smaller set of core services which also run during the off-peak and weekend.

- NYC Ferry runs a dense network on the East River and along Brooklyn’s shores (plus a Hudson River route to Staten Island)

- Seastreak runs services to the Jersey Shore; these are mostly peak-only, but there are handful of mid-day and late-evening trips sprinkled in, plus a Sandy Hook Beach service that mostly runs on weekends

- Liberty Landing City Ferry runs to its namesake, with an additional stop just across the Morris Canal at Warren St in Jersey City (which I omitted here, bowing to the challenges of a complex diagram)

- Statue City Cruises runs ferries to Liberty Island and Ellis Island, primarily between 9am and 5pm, though with some later evening departures available from the islands only

- The Trust for Governors Island runs a network of routes, alongside a weekend-only route run by NYC Ferry

- The famous Staten Island Ferry is run by the NYC Department of Transportation

NYC Ferry and the Staten Island Ferry are publicly owned, while the rest are privately owned.

Beyond the companies listed above, there are also excursion and sightseeing ferries, but I drew the line at drawing those lines on the map. (Ha.)

For those who are interested, some details on frequencies, this mapmaking process, and analysis of this ferry system in the context of others, below.

Frequencies

- NY Waterway operates on the Hudson, with criss-crossing network of peak-only services and a smaller set of core services which also run during the off-peak and weekend.

- The all-day services usually run on 20-minute frequencies,

- while the peak-only services are usually every 30 or 40 minutes.

- The Paulus Hook <> Brookfield Place route runs on 15-minute frequencies, except during the morning peak when it increases to 7.5-minute frequencies

- NY Waterway also runs two services much further north, connecting cross-river to Metro-North’s Hudson Line

- NYC Ferry runs a dense network on the East River and along Brooklyn’s shores (plus a Hudson River route to Staten Island)

- Most routes run approximately 45-minute frequencies, with some falling to 60 minutes off-peak, and the Staten Island and Hunters Point South routes increasing to 20-25 minutes during peak

- Seastreak runs services to the Jersey Shore; these are mostly peak-only, but there are handful of mid-day and late-evening trips sprinkled in, plus a Sandy Hook Beach service that mostly runs on weekends

- Frequencies vary widely, but usually see an hour or more between departures

- Liberty Landing City Ferry runs to its namesake, with an additional stop just across the Morris Canal at Warren St in Jersey City (which I omitted here, bowing to the challenges of a complex diagram)

- This route runs hourly from 6:30am to 7:00pm

- Statue City Cruises runs ferries to Liberty Island and Ellis Island, primarily between 9am and 5pm, though with some later evening departures available from the islands only

- The New York route runs on 25-min frequencies on weekdays, which gets bumped to 20-min frequencies on weekends and holidays. The New Jersey route runs every 35-40 minutes

- The Trust for Governors Island runs a network of routes, alongside a weekend-only route run by NYC Ferry

- Its Manhattan Route runs daily with half-hour frequencies most of the day

- The weekend-only routes to Brookyln run hourly

- The famous Staten Island Ferry is run by the NYC Department of Transportation

- This service runs 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, with 30-min frequencies off-peak that rise to 15-20-min during peak

Almost none of these services run SUAG (“show up and go”) frequencies, with the exception of peak Paulus Hook <> Brookfield Place service, which bops back and forth between Jersey City and Downtown (only 4000 feet apart) every 7.5 minutes during rush hour.

The higher-frequency services might be considered “SUAW” (show up and wait). Many of the ferry terminals are enclosed, with seating and sometimes light food options, making a wait more tolerable. Other routes do not reach this threshold, and a traveler must take the schedule into account when planning journeys.

Larger Implications

Ferries are cool but weird, embodying a cool but weird tension in our urban spaces.

In an earlier era — we might call it the “modern era” or the “industrial era” or the “pre-war” era –, cities grew up around water. Rivers were transportation corridors, harbors were doorways to the rest of the world. Being close to the water was an unambiguous asset.

In the current era — “post-modern”, or “post-industrial”, or “post-war” –, water has lost its primacy and now vies among a family of other factors in shaping our cities. Being close to “pretty water” is an asset to commercial and residential development, but being close to “industrial water” is a strong negative. Water becomes an obstacle for transit to build around or navigate through, seen as a constraint rather than an enabler of mobility.

Where cities were once drawn to water, now it is often a neutral or slightly repelling force, as cities instead develop in other directions. This in turn impacts transportation.

Boston had a dramatic example of this: the Atlantic Avenue Elevated, built along the city’s wharves, stupendously underperformed as water’s royal status was gradually revoked in the early twentieth century. With the docks no longer a transportation center of gravity, the El became a rapid transit route whose walkshed was half water. Its demolition seems inevitable in hindsight.

For ferries to work at large scale, they need to be connected to unusually strong centers of gravity. This is visible in New York’s ferry network, which is heavily weighted toward Lower Manhattan. For many commuters, the ferry is probably their last mode of transit before walking the last few steps to work — there are just that many jobs crammed into Downtown, within a 10 minute walk of the pier.

The problem with ferries is illustrated by NY Waterway‘s free bus shuttle network, which radiates out from their Midtown West pier, running along major cross-streets to 3rd Avenue. The edge of the traditional core of Midtown is about a mile inland, limiting the ferry’s ability to get people where they need to go. A subway can travel under both water and road, creating a seamless journey where the ferry requires a transfer.

(New development around, for example, Hudson Yards, is increasing the ferry’s usefulness, of course, which reflects a larger trend in New York’s ferries: they often connect to formerly industrial redeveloping areas.)

The continued role of ferries is illustrated by NY Waterway’s full-time network (seeing 20-min headways all day) and the Staten Island Ferry (with 15-30 min headways 24/7): crossing water that lacks bridges and tunnels. Along New York City’s entire 14 mile Hudson shore, there are only six fixed crossings, most of which are in the southernmost four miles. By contrast, the East River has eight crossings just in its southernmost two miles (from the Williamsburg Bridge to the subway tunnels). The Hudson ferries essentially double the number of cross-river connections.

Ferries will probably never again enjoy the popularity of their heyday. But, at least in New York, they clearly still have a part to play.

Design Process

This is another early attempt at mapmaking using Illustrator. (Very late to the party.) From a design perspective, there were two key challenges (beyond the logistical challenge of finding, cataloguing, and untangling the web of overlapping services).

First, the scope and scale. The distant edges of the network stretch anywhere from 12 to 20 miles away from Downtown. At the same time, most of the network was constrained to a much smaller area. And in terms of mapping, the real painpoint is a pair of very small areas where there are lots of overlapping routes (the lower Hudson and the mouth of the East River), with extra space required to accommodate the necessary level of detail.

The physical nature of the ferry network meant that the diagram would inevitably have a bare minimum of geographic fidelity. But I tried not to provide much more detail than that — not only to simplify my own work, but to avoid the appearance of more precision than intended. For example, Paulus Hook, Liberty Harbor, and Liberty Landing are all a stone’s throw from each other. In fact, “The Battery/South Ferry/Whitehall” as I’ve drawn it is actually a consolidation of three terminals that are pretty far apart. In both cases, the contraction and expansion of geography was needed in order to show complicated service patterns clearly.

The second challenge was the range of service levels that needed to be readily distinguishable. I wanted the full-time network to be immediately visible and unambiguously distinct from the other services. In practice, this meant that I had to come up with three visual tiers “below” a “standard full thickness” line similar to what I’d use on a subway diagram. I opted to use two dimensions to create the four levels: weight and solid/dashed. How effective that strategy was is a question I will leave to the reader.

Finally, one unexpected challenge was the multiplicity of names used for “stops”. Some of this challenge was self-imposed, such as the aforementioned consolidation of The Battery, South Ferry, and Whitehall Terminal. But, for example, nearly all of the NY Waterway piers had double names, such as Pier 11 Wall Street or Brookfield Place/Battery Party City. In some cases, their second name was an indication of their city — for example, the two piers in Weehawken. This was a convention I expanded a bit, such as including Staten Island alongside St. George.