I believe extending the Blue Line from Charles/MGH to Kenmore via a Riverbank subway along Storrow Memorial Drive is the stronger “first phase” extension.

The truth of the matter is that we don’t have enough data to say which is better. As I’ve outlined above, almost any extension of the Blue Line west will be treading new ground, bringing rail transit to corridors that have never seen it before. This is virtually unprecedented in the history of Boston transit, so we are in uncharted waters.

Any construction at Charles/MGH should be done to leave open as many possibilities for future extension, including both to Kendall and Kenmore if possible; if a choice must be made, my preference is for Kenmore.

I have are four overarching reasons:

Complementing the Green Line

As outlined previously, the Blue Line and the Green Line have a long historical relationship of interdependence and interweaving. The Kenmore alignment maintains that relationship, and provides relief for the Green Line, freeing it up to adapt to the flexibility offered by LRT without needing to bear the burden of being a pseudo-HRT subway line.

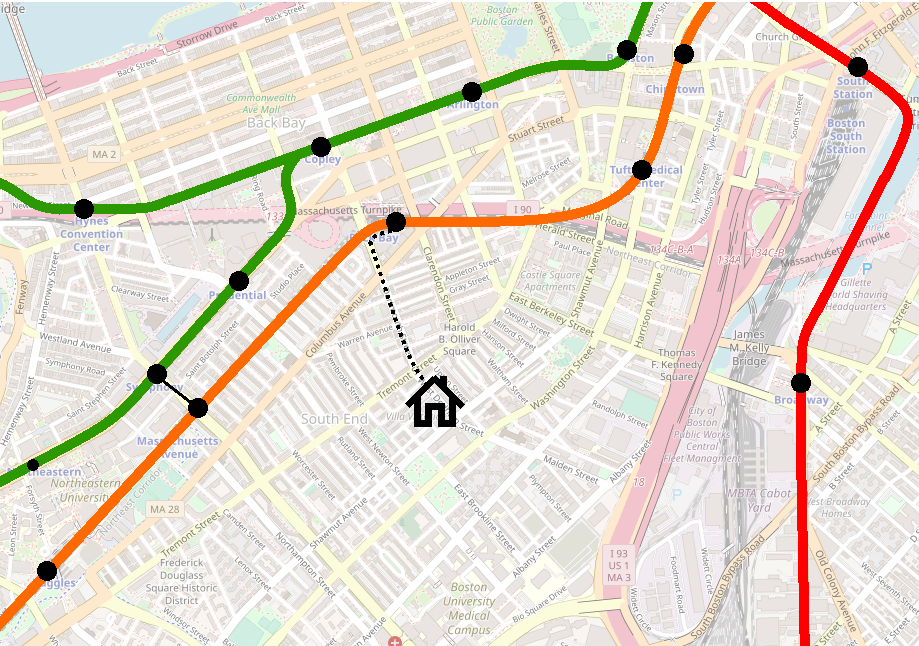

The Riverbank alignment sends the Blue Line straight down the middle of the gap between Red and Orange, landing it at Kenmore – the major bus transfer hub between Central and Ruggles. This is where the Green Line’s burden would be relieved: it would no longer need to serve as the radial link between the Kenmore hub and downtown.

I have a large and expansive vision for the future of the Green Line, and many more options are opened up through the Kenmore alignment than the Kendall alignment.

Filling a gap in the HRT network

We often think of the MBTA as having 4 subway lines, plus a handful of BRT lines. Strictly speaking, that is not quite true. The MBTA has 3 heavy rail lines, a handful of light rail lines, and a handful of BRT lines. The T uses layered LRT and BRT services as stand-ins for HRT services in the Boylston Street Subway, the Tremont Street Subway, and the Piers Transitway, because the ridership along those corridors demands it, but they still are different beasts.

The future of expanded rail service in Boston lies in LRT and in frequent regional rail. These services are easier to create because they are either easier to construct or are better able to leverage existing infrastructure. With a small number of exceptions (Lynn, Arlington, Mattapan, and West Roxbury), bringing rail service to new locations will be much easier to do with LRT and regional rail (Needham, Watertown, Jamaica Plain, Waltham, Lexington, Grand Junction, Everett, Chelsea, and Dorchester).

Heavy rail rapid transit provides best-in-class service, there is no denying it. But it also requires the most up-front expense, and is rapidly becoming a form of boutique construction – a Blue Line extension will be usable by Blue Line trains alone, while new stations and improved tracks along the Worcester Line will be usable by metro Indigo Line services, local Framingham services, and expresses to Worcester (and will benefit Amtrak service to Springfield and beyond). Heavy rail expansion therefore must meet a higher threshold of viability and benefit.

As such, I think we need to reconceptualize our idea of Boston’s rapid transit system into three tiers: light metro, heavy metro, and regional metro.

- Light metro: LRT and BRT services, with smaller vehicles and smaller infrastructure footprints, particularly useful for suburban radial service and urban circumferential service

- Heavy metro: your standard HRT, as well as rapid-transit-frequency mainline rail, and Los Angeles-style light rail (e.g. longer trains, high-level boarding, dedicated ROWs).

- Regional metro: reimagined commuter rail – 15-minute headways, limited stops within 128, service to suburbs and satellite cities.

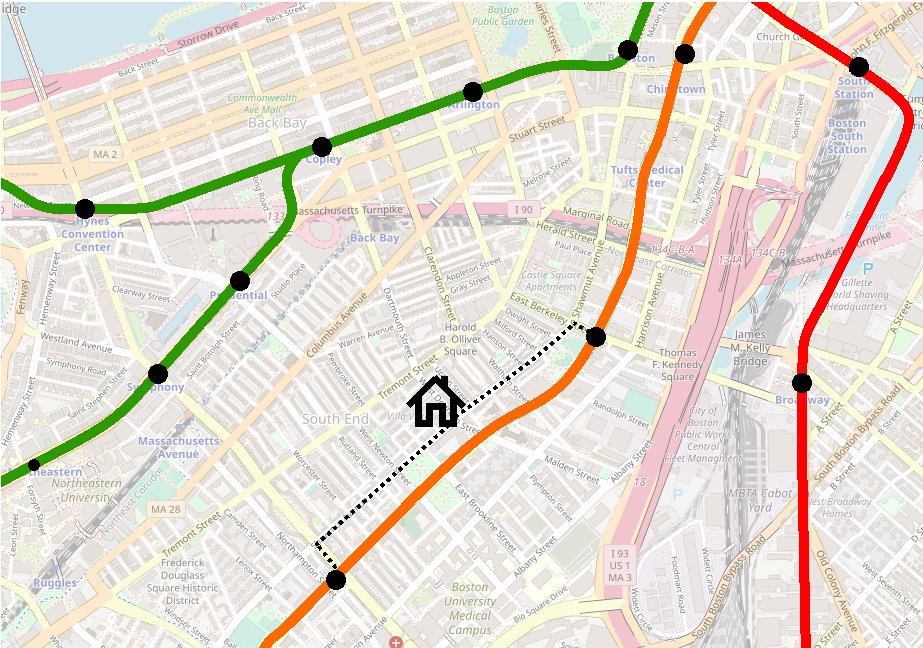

These tiers are obviously interconnected, but do form distinct networks. And I believe we need to view them as such. As can be seen here, any Blue Line West extension will serve to fill in the large gap between the Red Line and the Orange Line.

When we exclude light metro services from the map, the gap in the heavy metro network becomes clear. The streetcar services that run into Kenmore from Beacon and Commonwealth will always prevent that stretch of the Green Line from becoming proper heavy metro, which means an alternative is sorely needed to fill in the gap.

As mentioned above, the future of rail expansion is in LRT, not HRT. Wholesale greenfield rail construction in Boston will mostly be LRT going forward. HRT expansions should therefore be sparing, and strategic, benefiting the entire network as a whole as opposed to specific corridors. Extension to Kenmore balances the heavy metro network overall, and frees up capacity on the Green Line to expand the light metro network into new areas across Greater Boston.

Put heavy metro service to its unique purpose

Let’s hearken back to the days of the El. You live on West Dedham Street in the South End, halfway between Shawmut and Tremont, a block and a half from Washington Street – you can see the El from your front door. A generation goes by, and the Orange Line is relocated out of sight, a bit less than a half mile away in the Southwest Corridor. On the balance, you’re pretty happy – the El was loud, rumbly, an eyesore, a relic of an age past.

But isn’t the loss of transit access a downside? (You are asked by your railfan friend.) Not really, you reply. Even though the El was a three minute walk away, it was nearly 10 minutes to the nearest stations, at Dover or Northampton. The El rumbled by your block every day, speeding through without making a stop. The new station at Back Bay is just as long of a walk, but now Washington Street is sunny and quiet(er). On the balance, you’re pretty happy.

(At various points through the 20th century, you might not have walked to the El at all, but instead caught a streetcar or bus at surface level and rode that in.)

The same was true in Charlestown: for nearly three-quarters of a mile along Main Street, the El expressed through, while local residents took the 92. Sullivan, with its massive hub of transfers from Everett, Malden, Medford, and Somerville, was the objective, not the northern half of Charlestown itself. Main Street suffered the drawbacks of rail infrastructure, and for the most part got none of the benefits.

To be clear, I am not claiming that the Orange Line Relocation Projects were net improvements for transit access; the sad story of Equal or Better makes clear that there were drastic downsides that persist to this day. My point is that the Relocation Projects demonstrate that the purpose of the early rapid transit lines was not to serve the neighborhoods they passed through, but to offer a bypass to enable faster journeys to downtown.

The primary role of heavy rail in Boston has historically been to whisk riders in to downtown from the Inner Belt regions and beyond. This is why the Red Line has such lengthy distance between stops in Cambridge, and why the extension beyond South Station headed down along Dorchester Ave instead of heading into Southie: the whole point was to express in to downtown.

Prior to the Orange Line relocation, the “Inner Belt” transfer hubs – with the exception of Kenmore – were at most two stops away from downtown: Dudley-Northampton-Dover-Essex, Kendall-Charles-Park, Sullivan-Community College-North Station, Maverick-Aquarium-State, Columbia-Andrew-Broadway-South Station. All those intermediate stops were themselves major transfer points or at major destinations. The whole point was to speed the journey downtown from the outer parts of the city, whence a bus or streetcar journey would be painfully long.

A Blue Line extension to Kenmore fills that gap, and provides the western feeder services (the B, the C, the 57, the 60) with a proper heavy metro express link into downtown, providing a speedy and reliable transfer consistent with similar hubs across the system. This need exists at Kenmore, but does not exist on the other side of the river.

Follow existing ROWs and generally have easier construction

To my knowledge, with three exceptions, all expansion of Boston rail infrastructure in the last 100 years has occurred on alignments and ROWs which were carved out by railroads in the 19th century. (The three exceptions are Harvard-Davis, the stretch between Chinatown and the portal east of Back Bay, and the Huntington Ave Subway.) The Blue-Red Connector would mark the fourth such exception.

It is incredibly difficult to build rail where none existed before, and it is incredibly rare. The Huntington Subway was decades in planning, Harvard-Davis was built under exceptionally favorable political circumstances, and the Orange Line connection was the lynchpin in a massive service relocation that had been in the works since the 1900s. Virtually no current expansion proposals – official or amateur – call for laying rails where none have been laid before. (The North-South Rail Link is the exception that proves the rule in this case.)

Blue Line West proposals are the only ones where we consistently see greenfield ROWs being proposed. For the Phase 1 alignments I discussed before, this is a necessity – there simply is no way to continue west from Charles/MGH without building new ROWs. Several of the Phase 2 alignments, however, do leverage existing ROWs.

The “Phase 2” alignments I discussed earlier fall into three categories: Watertown, Mass Pike, and Longwood. Kenmore offers access via existing ROWs to all three, due to its location at the confluence of the Highland Branch and the B&A (Worcester Line) ROWs. (Watertown would be the trickiest of the three, but still could utilize the B&A ROW for at least half of the journey.)

The Kendall alignments are more of a mixed bag. Longwood technically could be accessed from the BU Bridge via a subway under Amory Street, but at significant expense and with some tricky track geometry (i.e. sharp turns). Watertown and the Mass Pike could be reached via Kendall, the Grand Junction, and the BU Bridge, largely utilizing extant ROWs, but at the cost of two river crossings and the lack of access to the Kenmore transfer hub. (Circumferential service from a Kenmore hub to Longwood, Ruggles, and Nubian would be pretty easy to plan with BRT. Relocating the transfer hub to a Blue Line station at BU Bridge would be more difficult.)

One hundred years ago, the mainline gateway to Boston’s western suburbs was located in the Fenway at Brookline Junction station. Despite all that has happened in the intervening century, the ROWs that were laid out feeding into that junction have persisted over all these years. Because of that, Kenmore has remained a transit nexus, and remains the strongest “launchpoint” for any future expansion to the west.

Conclusion

Basically this all boils down to “serving Kenmore” vs “serving Kendall”. Both alignments can land you in Beacon Yard, setting the stage for service to Auburndale, Watertown, or Waltham. Both alignments could (at moderate-to-significant expense) lead to service to Longwood.

Kendall is a massive employment center, growing every year. Kenmore is a massive transfer hub that will only become more important as the T improves circumferential service. Kendall’s Red Line service is at capacity; Kenmore’s Green Line service is at capacity.

To a certain extent, I’m sufficiently convinced in favor of the Kenmore alignment by the added cost and expense of the dual river crossings needed for any Kendall alignment. Greenfield HRT is going to be hard enough on its own – at the very least, let’s choose the easier option.

But beyond that, I think the Kenmore alignment is simply better for the whole network overall. The Kendall alignments would benefit their immediate corridors, while a Kenmore alignment’s effect would be felt system-wide.

- Consolidating Kenmore as a transfer hub makes it easier to build a flexible Urban Ring, in stages if needed.

- Complementing the Green Line frees up resources to be redirected into a semi-heavy metro corridor along Huntington, and creates more flexibility for short-turning LRT services at Kenmore.

- Focusing construction efforts along the Grand Junction on LRT rather than HRT creates a potentially unbroken LRT corridor from Allston to Cambridge to Sullivan to Chelsea to the Airport.

- And a Phase 1 extension to Kenmore leaves open the most possibilities for Phase 2 extensions without the need for massive tunneling projects.

All of this is many years, if not decades, in the future. For now, I reiterate my original point: Any construction at Charles/MGH should be done to leave open as many possibilities for future extension, including both to Kendall and Kenmore if possible; if a choice must be made, Kenmore is the stronger option.