This page will be updated with additional maps and diagrams. See details in text below.

Contents

E Line Subway

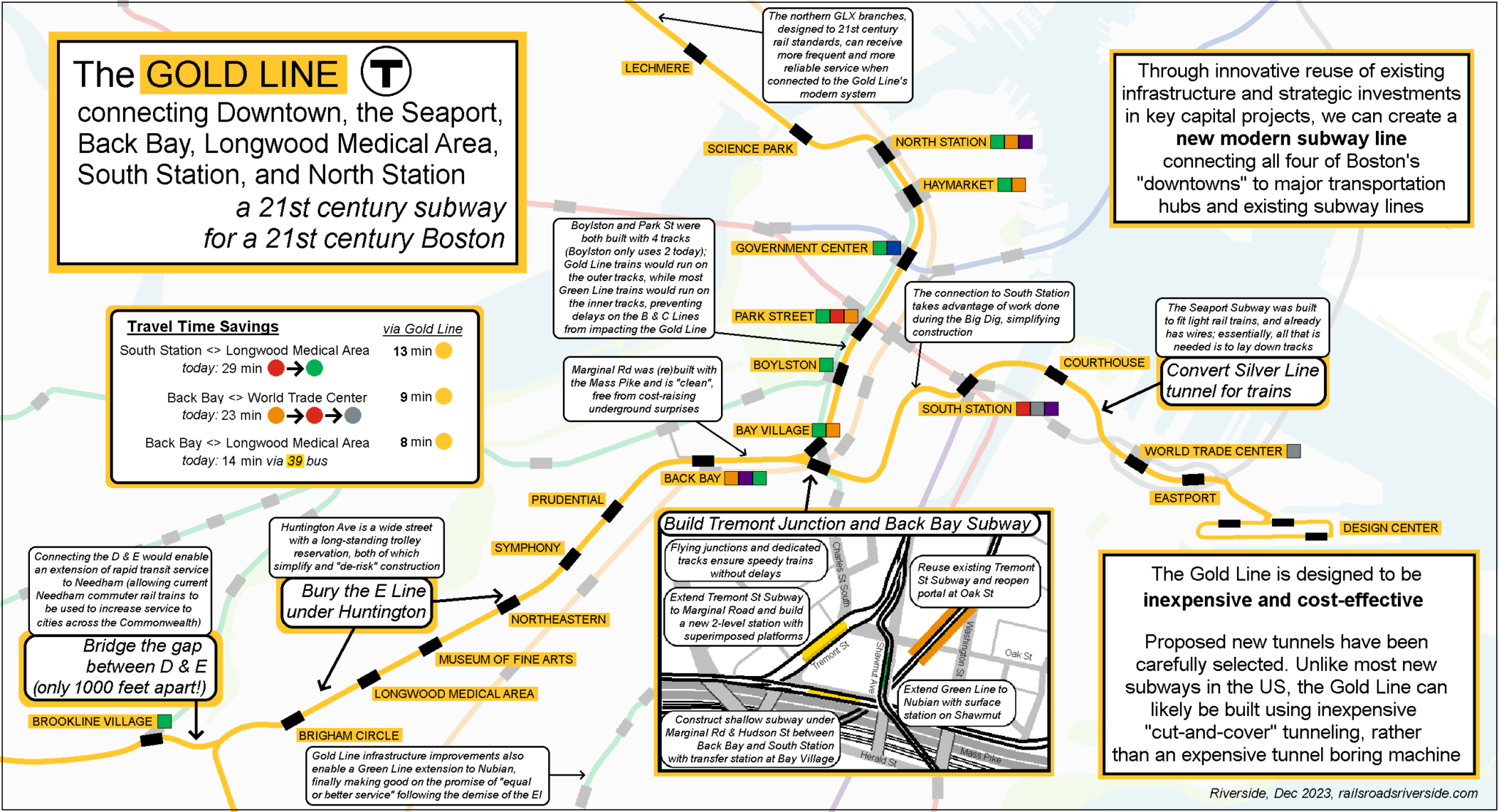

The E Line is the little engine that could. As the primary rapid transit service to Longwood, it shoulders the heavy burden of serving the equivalent of Downtown all on its own.

The four stations from Northeastern to Brigham Circle (including the stops at Longwood Medical Area) serve as many riders in 1 mile as the entire C Line does across its 2.5 miles. Yet, because of traffic lights and pedestrian crossings, the E Line crawls along at less than 8 miles per hour most days.

The E Line should be in a subway, at least as far as Brigham Circle, if not farther. In fact, original designs from the 1920s called for exactly that; even 100 years ago, it was clear that Longwood deserves a subway.

The good news is that Huntington Ave would be one of the easiest places in the city to build a new subway. The road is very wide, giving construction crews the ability to work without blocking traffic. The existing trolley reservation in the middle of the street provides space for construction equipment. And the fact that the reservation has been in place for over 100 years means that it’s much less likely that the construction crews will make surprise discoveries (such as unmapped utility lines, pipes, or historical artifacts), which is a major driver of high construction costs.

Building a subway under Huntington would make the E Line faster, more reliable, and would allow the MBTA to run more frequent trains, all of which will support the continued growth of Longwood. As part of the Gold Line, a Huntington Avenue Subway would provide benefits that stretch across the entire reason, as you’ll see below.

The Back Bay Subway and Resurrected Flying Junction

One of the biggest challenges faced by the Green Line in terms of capacity and reliability is the “flat junction” at Copley, where the E joins the B, C & D. A flat junction is like a street intersection; trains often have to stop to let traffic cross through the junction, just as traffic waits at red lights.

The earliest parts of the Green Line were not built with flat junctions, but rather with “flying junctions”. These are like highway interchanges: tracks never cross each other, and no one has to wait at a red light. Flying junctions let trains run faster, more often, and more reliably.

The Green Line has an unused fully intact flying junction at Boylston station. If you have ever wondered what the two fenced-off tracks behind the platform are for, this is it: they lead south through a flying junction (the outbound track dives underneath the current Green Line tracks; if you peer through the fence at just the right place, you can still see it), and originally ran to a portal in what is now Eliot Norton Park, from which streetcars exited and ran through the South End and Southie.

By connecting the existing E Line subway (at Prudential) to the flying junction at Boylston, all four branches would be able to run faster, more reliably, and more frequently, because trains would no longer have to wait for each other at the “red light” at Copley.

This is a good illustration of a key tenet of the Gold Line, and the Green Line Reconfiguration overall: targeted projects that would have systemwide benefits.

Connecting to the flying junction at Boylston would require two pieces:

Back Bay Subway

First, a subway hugging the northern side of the Mass Pike would be built from the intersection of Huntington & Stuart, through Back Bay Station (providing a transfer to the Orange Line, Commuter Rail, and Amtrak), and beyond to the intersection of Tremont & Marginal Road (less than 3000 feet long).

Like the new E Line subway, this route is designed to be inexpensive. When the Mass Pike was built, the ground to the north was dug up and then put back, meaning that the underground utilities have either been mapped or relocated away entirely, and therefore meaning that tunneling will be much easier, since we know what’s there and have done it before.

Bay Village

Starting at Tremont & Marginal comes the second piece: a short subway running under Tremont St for less than 600 feet to Eliot Norton Park, where it would join the abandoned-but-intact original Tremont St Subway, which connects directly to the flying junction at Boylston. A new station would be built between Marginal Road and Eliot Norton Park, which I will call “Bay Village” station; this station will become very important later on. Additional details here.

Extending the original Tremont St Subway down to Marginal Road with a new station would be somewhat more complex and expensive. However, the distance is quite short, and we get tremendous “bang for our buck” because we can reactivate the original Tremont St Subway, an entirely unused subway over 1000 feet long, sitting right under our noses. And as you will see, this short connection becomes the lynchpin in a systemwide transformation.

A Faster Stronger Bolder E Line

With a full subway under Huntington connected to the flying junction at Boylston via Back Bay and the original Tremont St Subway, the E Line — and in fact the entire Green Line — would be transformed.

Trains would be able to zip from Downtown to Back Bay to Longwood at close to twice the speed of today. New accessible subway stations would allow all riders to quickly board and alight from trains, able to wait in a safe comfortable space, protected from the elements and the traffic. With longer, larger platforms, the T would be able to run longer trains, increasing capacity of the subway. And dedicated tracks, unencumbered by street traffic or train traffic, would allow trains to run more frequently and more reliably.

Meanwhile, trains from the B, C, & D will be able to run uninterrupted from Kenmore into downtown, making for faster journeys and more reliable service. The legacy “streetcar-subway” services on the B & C would be largely isolated from this new modern subway, allowing all branches to run according to their original design, instead of trying to contort themselves into something they aren’t.

The D-E Connector: an 8 mile extension in 1,000 feet

The D Line is not like the other branches of the Green Line. The B, C & E all used to be local streetcars, similar to buses. But the D was actually a commuter rail line, for over 80 years, before it was converted into a rapid transit line in the late 1950s.

As a result, the D Line has larger stations, spaced farther apart, running all the way to Route 128. Trains are able to run at high speed between stations, and in general the D Line has more in common with the new Medford/Tufts branch than any other branch.

The E Line’s Riverway station (at Huntington & South Huntington) is about a 7-minute walk from the D Line’s Brookline Village. At their closest point, the D and E Line are less than 1,000 feet apart.

Our new faster stronger bolder E Line is a perfect match for the D Line. With a short extension to connect the two, the new Gold Line would triple in length, providing a one-seat-ride between Downtown, Back Bay, Longwood, and the Route 128 park-n-ride at Riverside. The existing D Line stations would require no upgrades or improvements; connecting them to the Gold Line would simply allow them to reach their full potential.

Gold Line to Needham

Integrated with a modern subway under Huntington Ave, the Gold Line would be able to add a new branch to Needham, splitting off at Newton Highlands and traveling south to absorb the last three stops on the Needham Commuter Rail line. This would significantly increase service to Needham, with Gold Line trains able to run much more often than the Commuter Rail.

(The Green Line can and should be extended to Needham, even without the Gold Line. However, the Gold Line will be able to operate at significantly higher frequency and higher reliability than a Green Line extension could.)

Commuters from across the state should cheer the conversion of the Needham Line from commuter rail to rapid transit. Why? Because Needham Line trains take up valuable space on the same tracks that run trains to Providence, Stoughton, Franklin, and eventually Fall River and New Bedford. Converting the Needham Line to rapid transit would free up capacity, allowing more frequent commuter rail service to cities across the commonwealth and beyond.

The Gold Line: A Subway to the Seaport

The Seaport already has its own subway: the Silver Line tunnel. However, the subway is currently an orphan, connecting only to the Red Line at South Station, and with a single portal in the eastern end of the Seaport. By bridging the gap to South Station, the Gold Line can unlock the full potential of the Seaport Subway.

From the new station at Bay Village, a second branch of the Gold Line would continue parallel to the Mass Pike, then curving north under Hudson St. From here, it would run parallel to the Big Dig tunnels (through an underground area that is well-documented) before turning under Essex St to join the existing Silver Line tunnel. The Silver Line tunnel includes a provision for the never-built Silver Line Phase III, meaning that the tunnel is ready built to be connected to a new subway.

The Silver Line tunnel was built to fit trains, even though the original plan was only for buses to use it. The tunnel was also already built to include overhead wires. Essentially, all that would be required to run Gold Line trains through it would be lay down tracks. (The reality will of course be a bit more complicated, but the fact remains that the hard part — building a tunnel — has already been completed.)

At the far eastern end of the Seaport, Gold Line trains may continue at street level to Design Center, or that route can continue to be handled by Silver Line buses.

In a generation or two, a Gold Line Seaport Subway could be extended under the Harbor to Logan Airport. This would mean that every transportation hub and all four of Boston’s “downtowns” would have a stop on the Gold Line: Logan Airport, Seaport, South Station, North Station, Downtown, Back Bay, Longwood, and a park-n-ride at the Mass Pike’s intersection with Route 128.

This would of course be much more expensive than anything else described here, so I consider it “out of scope.” But, this possibility illustrates the promise of the Gold Line: not merely serving the needs of Boston today, but laying the foundation to serve the needs of Boston tomorrow.